My thanks to Silviu Sergiu for his questions and publication of a two part interview with me. Here are the links to the Romanian language versions of the interview. Below that are the English language answers I sent Silviu for the interviews

Categorizing what kind of event happened in December 1989

Without the protests, uprising, and conquering of local power in Timisoara from 15-21 December 1989, there may not have been an uprising in Bucharest on 21 December 1989 and the overthrow of Nicolae Ceausescu on 22 December. However, without the overthrow of Nicolae Ceausescu, the Ceausescu regime probably would have crushed the Timisoara revolt, just as it had done two years earlier in Brasov. It is important to note that Timisoara’s Frontul Democratic Roman (FDR) was the first revolutionary group to achieve power, albeit only in the Banat.

The uprising had to spread to the capital, and the armed institutions of the Ceausescu regime had to transfer their allegiance to an “alternative polity,” to use Charles Tilly’s term, for the revolution to succeed. This happened on the afternoon of 22 December 1989. Although there were other attempts to form a revolutionary government, only the Council of the National Salvation Front (CFSN) was able to secure the majority support of the armed institutions of the Ceausescu regime, precisely because it was made up of the communist nomenklatura. The CFSN possessed a huge structural advantage that other groups did not have, and it inevitably stunted the anti-communist evolution of the Revolution. The CFSN’s seizure of power was a direct product of the Ceausescu regime’s repression, because it had prevented the formation of civil society groups that could come to power, as happened in Czechoslovakia for instance.

The Importance of the Terrorists to Understanding December 1989 and Pitu’s “False Flag” and “Friendly Fire” Arguments

The key questions about December 1989—and even retired military prosecutor Catalin Ranco Pitu acknowledges this in his 2024 book—is did the terrorists exist and, if they did, who were they, what were their goals, and who did they report to? In other words, who bears responsibility for the almost 1,000 deaths and 3,000 injuries after 22 December? Pitu maintains that what happened after 22 December was a coup d’etat and that the Army—with the understanding and agreement of Ion Iliescu and the CFSN—engaged in a “false flag” operation. The “false flag” meant that the Army “invented” the “terrorists” through a massive disinformation campaign and blamed the Securitate by use of the phrase “securisti-teroristi.” The Securitate—and even the Ceausescus, Pitu maintains—were thus “victims” and “scapegoats” of the Army’s “false flag.” According to Pitu, there were no real terrorists and all those who died or were injured were the victims of “friendly fire” among the military, Patriotic Guards, and armed civilians. The military leadership, we are told, purposely disinformed and gave conflicting orders to their subordinates to spark this “friendly fire.”

Pitu is unable to tell us why, if this was a standing military plan, nobody involved in the operation of the plan leaked the details; why the CI-isti didn’t know about it and didn’t inform the Securitate leadership; and why nobody in the military—officers or recruits—or among civilians came forward during and immediately after December 1989 to counter the Army and CFSN’s claims of “Securitate terrorists?” Nobody was willing to say publicly that as bad as the Securitate were, they were not responsible for the violence and mayhem after 22 December. The idea that nobody spoke at the time about what is supposedly so obvious today—the “false flag” and the non-existence of the “terrorists”—should raise immediate doubts in those who listen to Pitu.

Pitu’s “Logic”

Pitu and his promoters keep on appealing to the supposed “logic” of their position. They point out that X was arrested or called a “terrorist” by the crowd, but the suspect proved in fact to be innocent. For example, they cite the famous case of Cristian Lupu in Bucharest. What they seem to fail to understand is that for their argument to be logically correct, they must prove that all 1,425 people officially arrested as “terrorists” were innocent. By contrast, it is far easier, as we do, to logically argue that the “terrorists” existed. All we have to do is to demonstrate that one or two of those 1,425 were “terrorists.” One or two cases of people being wrongly identified as “terrorists” is therefore not the same as one or two cases of people being “terrorists.” For the first outcome—”no terrorists”—the researcher must keep digging until they have examined all 1,425 cases and determined that all 1,425 suspects were in fact innocent. This is why it is so important to the former Securitate that the military prosecutors negate that even one terrorist existed: if even one existed, then there are likely to be other “terrorists” among the 1,425 who were detained. Ultimately, however, the truth of the Revolution File is not a matter of logic, but a matter of the details found in those documents.

Pitu’s Falsehoods

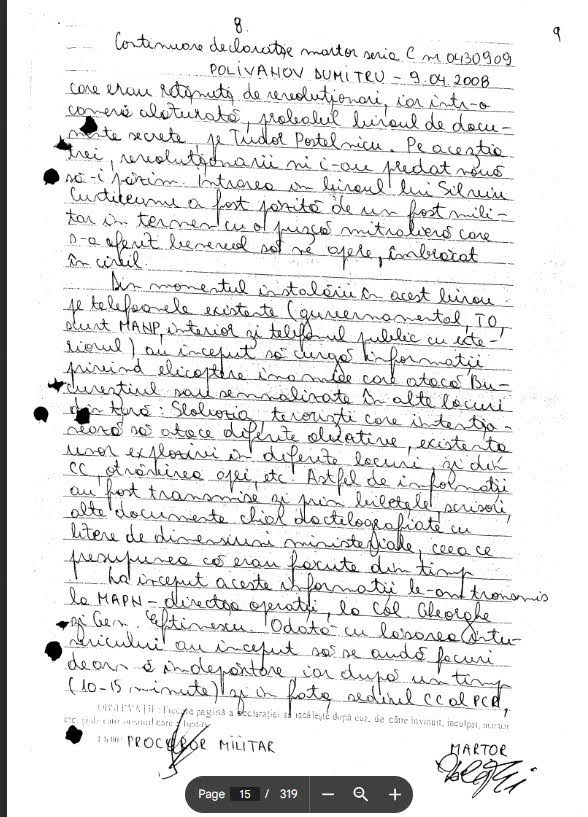

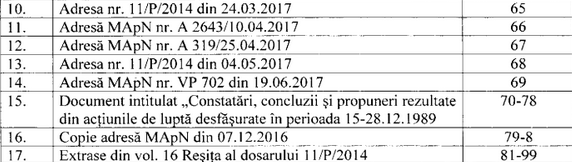

To demonstrate just how disingenuous Pitu’s claims are, let us look at a single file from the Revolution File, “Dosar revolutie nou.” This file includes depositions of different actors carried out in 2017 and 2018. It also includes many previously unseen, now declassified documents, especially from the military’s archive in Pitesti. In your interview with Pitu this summer, Pitu declared, “Fiecare structură din MApN, adică Apărarea antiaeriană, Infanterie, Tancuri, Informații Militare, Aviație Militară. Toate acele documente MApN, nu DSS, nu SRI, au demonstrat că fenomenul securist- terorist a fost un fenomen inventat de noua putere politico-militară a României, cu scopul obținerii legitimității și dobândirii impunității pentru unii din MApN.” On the contrary, the documents of these MApN structures which Pitu invokes, say exactly the opposite of what Pitu claims they say: they in fact say that the “terrorists” existed. I have posted these documents on my substack, https://richhall.substack.com/, so that anyone can draw their own conclusions about Pitu’s credibility and knowledge.

The Soviet role…or lack of one.

In interviews, Pitu has alleged that, “It is certain that in December 1989, 80 to 90 percent of those in the political-military group [CFSN + Army] who took power belonged to the [Soviet] GRU and KGB”; in fact, that “all 40 generals who were reactivated after 25 December 1989 have been documented as GRU or KGB collaborators.”

This begs a basic question: what were the Securitate doing prior to December 1989? Wasn’t it their job—especially the CI-isti—to catch spies? The Securitate did not notice all these KGB or GRU agents or did not surveil, interrogate, or arrest them? Who prevented them from moving against these supposed agents? Pitu’s numbers are simply ridiculous, but no one has challenged him on this claim.

Similarly, regarding the alleged “Soviet tourists,” if the Securitate were so suspicious, why did they not monitor or expel them if they suspected them of being undercover agents? Typical of Pitu is that he muddies the water. He claims there is no proof of the involvement of “armed foreigners” in December 1989, but then accredits UM 0110 Securitate Deputy Vasile Lupu (“martorul L. V.”, Rechizitoriul, pp. 304-305) when he invokes what Lupu has said about the tourists. As far as I can see far from being Soviet undercover agents, the “tourists” were likely of three kinds: 1) Soviets driving to Yugoslavia to sell their LADAs and other cars and then returning home (this is why they came back with multiple men in the same car—because they had sold the other cars with which they arrived in Yugoslavia); 2) convoys of Soviet cars (actual tourists) attempting to escape the violence and return back home (near Brasov and Sibiu I believe this was the case); and 3) a form of cover (acoperire operativa) used by the Securitate to be able to move around unnoticed in the event of a Soviet invasion. The 2,000 or 10,000 or 40,000 or 65,000 Soviet “tourists”–all supposedly let into the country and not monitored by the Securitate—is PURE FANTASY. I have traced the origins of this myth to the former Securitate and their collaborators in the media in 1990-1991, notably including former informant Sorin Rosca Stanescu and former Directorate Five Securitate officers.

Dr. Mark Kramer, head of Harvard University’s Cold War Studies Project, has probably performed more research in the Soviet archives than anyone else. He has not found anything to substantiate the accusations of Soviet involvement in December 1989, let alone of a planned Soviet invasion. One has to understand how ridiculous it sounds to a specialist on the Soviet Union, like Dr. Kramer, that the Soviets would have accepted the loss of East Germany and Czechoslovakia in November 1989—especially given the 350,00 Soviet troops based in East Germany—and done nothing to reverse it, only to intervene in Romania, a country of much less geopolitical importance, in December 1989.

The hard truth is that in the Soviet mind, Romania was comparatively unimportant: the Soviets did not care about Romania. They did not have the resources–personnel, cars–to devote anything approaching such numbers and they did not have the incentives to waste such precious resources on Romania. This will be difficult for many Romanians to accept, but it is the truth.

The documents we possess

Andrei Ursu and I have possessed a copy of the Revolution File (Dosarul Revolutiei) since 2021. Pitu routinely ignores this by only focusing on our 2019 book Tragatori si Mistificatori, and not our 2022 book Caderea unui dictator, which uses documents from the Revolution File. When Pitu talks about what is in the Revolution File, we know what documents he ignores in the Indictment (Rechizitoriul), in his 2024 book, Ruperea blestemului, and in the many interviews he has given since retiring in 2023. Much of what Pitu says is false and is contradicted by documents in the Revolution File.

The tactics of the “terrorists”

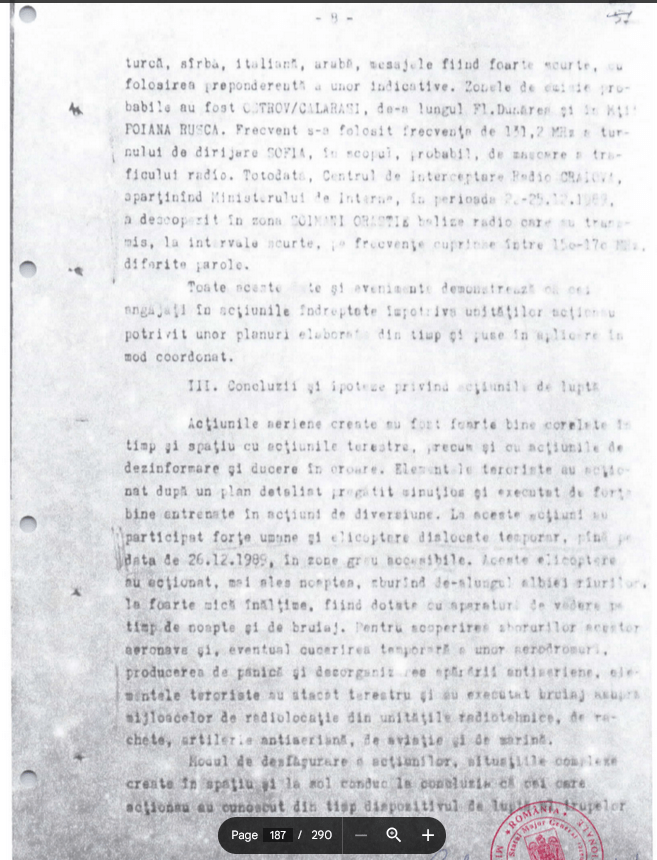

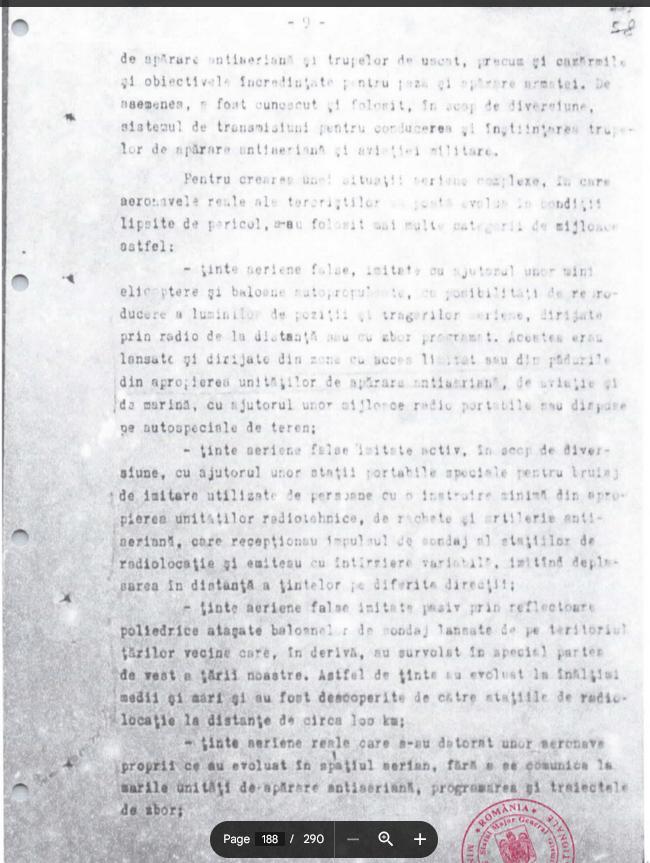

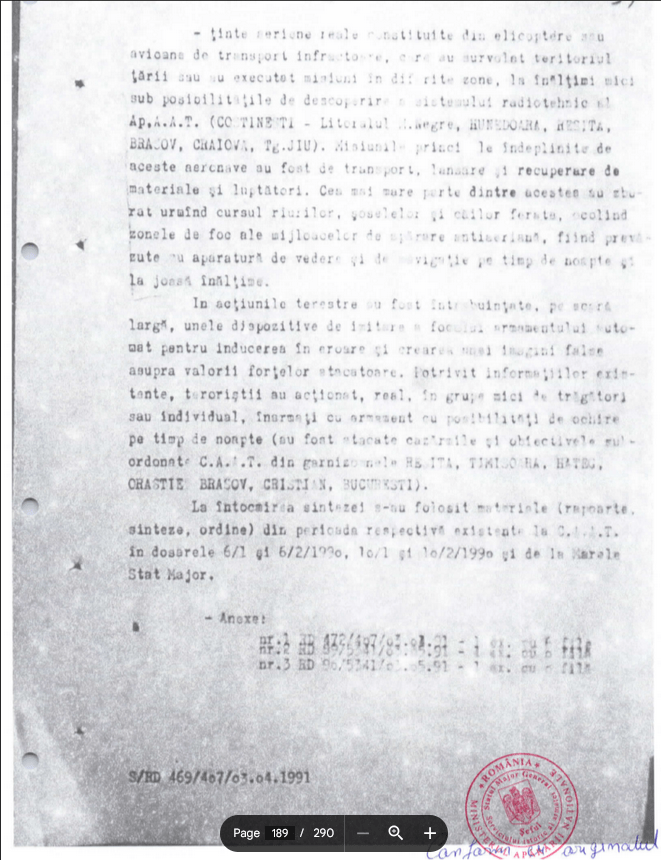

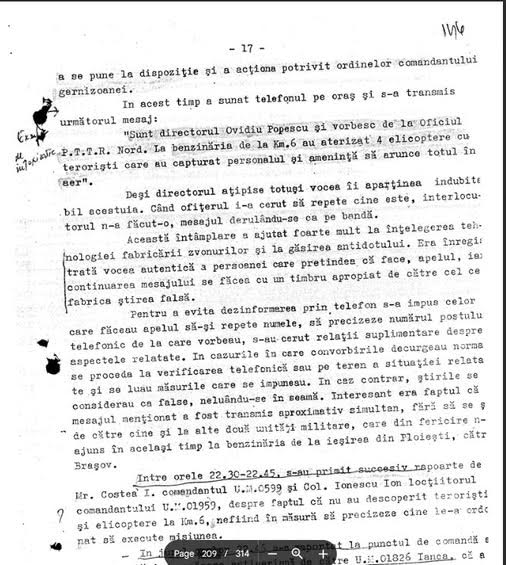

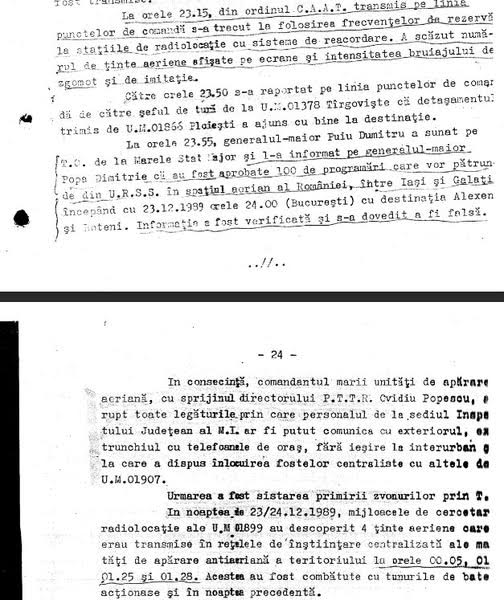

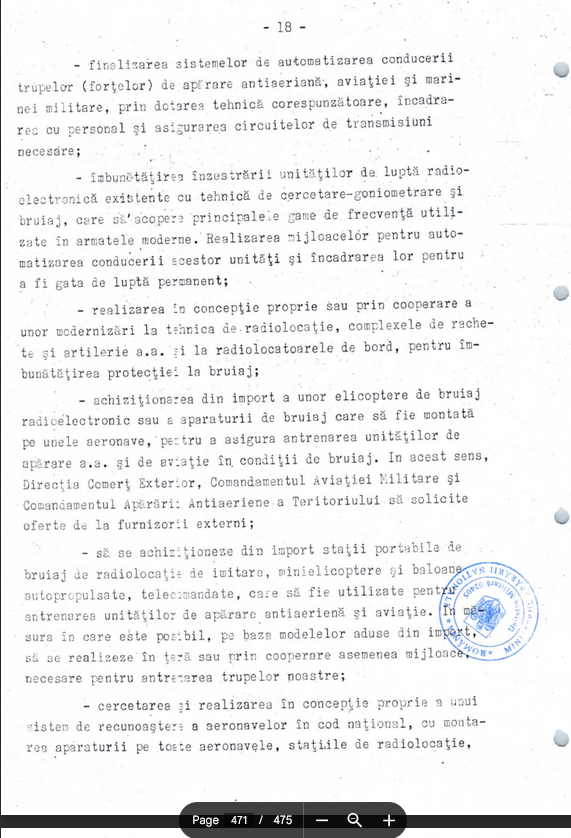

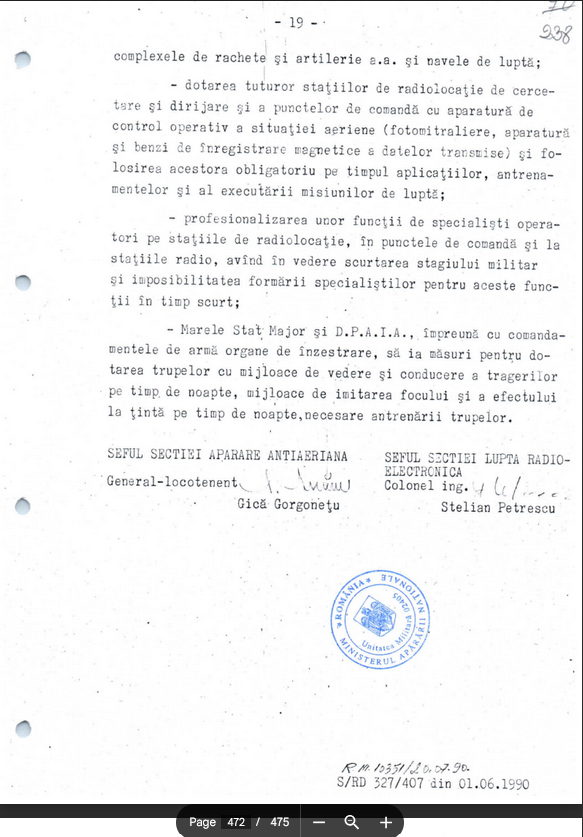

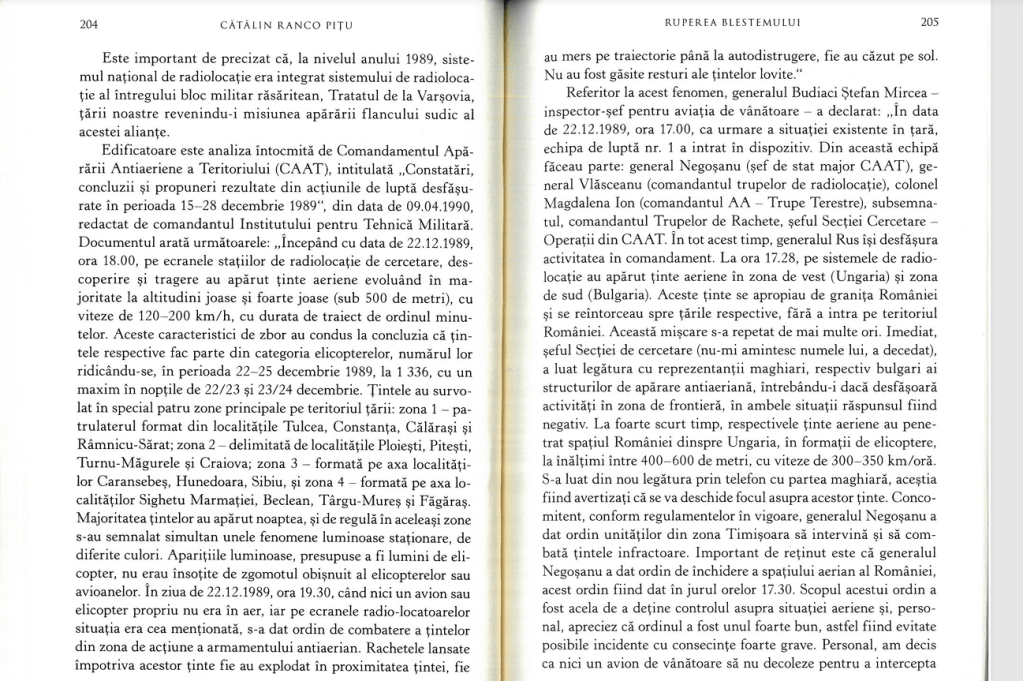

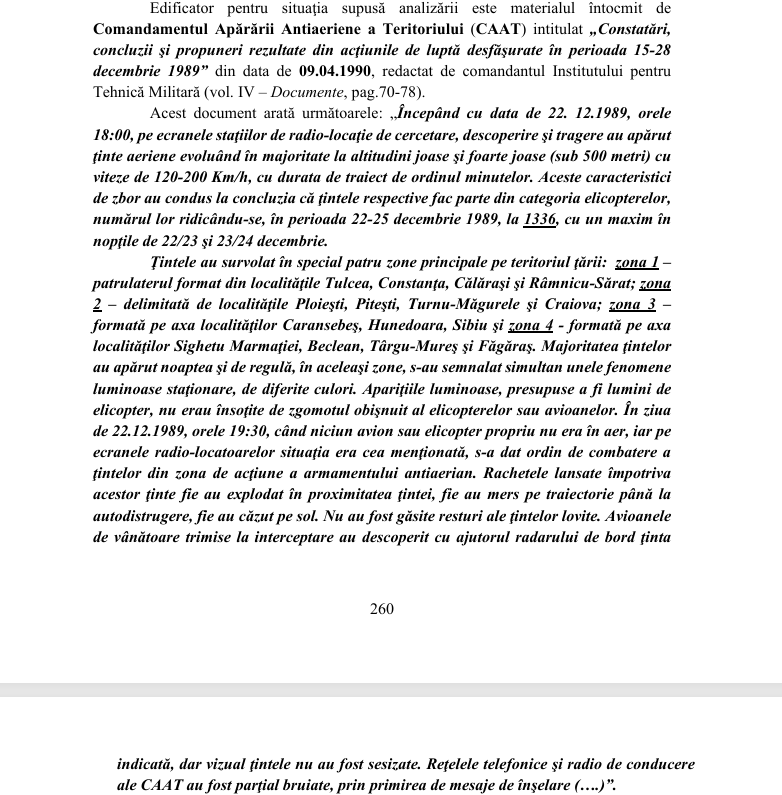

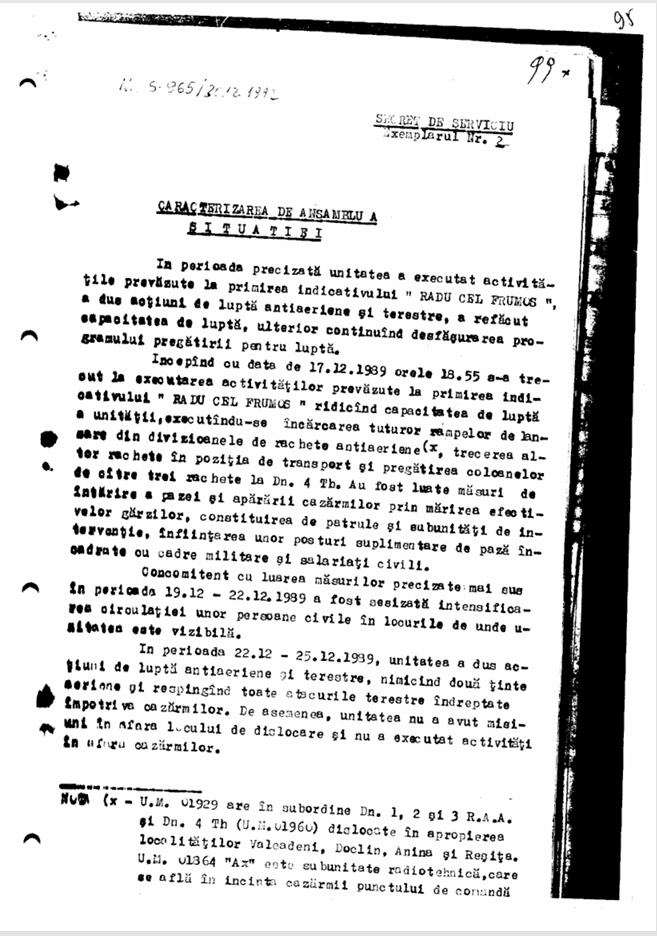

The “terrorists” of December 1989 existed. The “terrorism” of December 1989 had three main components: 1) Disinformation, by telephone, the spreading of rumors in person, and the interception and intoxication of military communications; 2) Radio-electronic warfare to make it look as if Romania were being invaded and that the enemy was more numerous than they in fact were, as well as the jamming of military communications; and 3) Sporadic episodes of gunfire, especially at night, designed to frighten, confuse, panic, exhaust, and keep the military pinned down in their barracks and the population in their homes. The latter followed the guerrilla tactic of “harassment and intimidation,” or as some military officers detected, “hit and run” or “strike and disappear” operations.

The “terrorists’” affiliation and what they said

Another point of “logic” that Pitu and his promoters appeal to is their conviction that once the Ceausescus fled the CC building shortly after noon on 22 December, everyone concluded that Nicolae Ceausescu was finished and therefore everyone, including the Securitate, abandoned him. We are told that it “wouldn’t be logical” for any Securitate members to attempt to save him. Therefore, they conclude, no one tried to save the Ceausescus.

This is highly problematic, since it is a retrospective judgment based on knowing the outcome of the events and working backward from the events to assess the actions of those who took them. Like the previous “logic” they appeal to, if their “logic” is correct, then there should not be any case of the Securitate acknowledging the existence of the “terrorists” or any confrontations or verbal exchanges with the counterrevolutionaries.

The Revolution File contains occasional verbal exchanges between those on the side of the revolution and the counterrevolutionaries. For example, at the antiaircraft battalion in Resita and in the Romarta building in Bucharest, the terrorists called those on the side of the Revolution “traitors” who had “violated their military oath” and had “betrayed Conducatorul [i.e. Nicolae Ceausescu].” The Deputy Foreign Minister recounts in a January 1990 deposition how two Securitate Directorate Five officers who were firing from inside the Foreign Ministry Building (MAE) told him they were shooting because 1) they were well-reimbursed and 2) they had taken an oath to defend the Ceausescus. Senior officials of the Securitate Troop Command who had joined the Revolution also discussed these two Fifth Directorate officers. Commanders who dispatched Securitate Troop officers to disarm the Fifth Directorate officers warned that the two were dangerous. In fact, when the Securitate Troop officers arrived on 25 December to arrest the two Fifth Directorate officers, it turned out they had far more numerous forces under their command than was believed and that they initially refused to surrender their weapons. Thus, even those elements of the Securitate not participating on the side of the counterrevolution at the time acknowledged the existence of “terrorists” who would not submit to the Revolution. Additionally, those present at the interrogation of the head of Directorate Five, Marin Neagoe, say that he admitted the existence of “the terrorists,” that they would continue to fight as long as the Ceausescus remained alive, and the location from which they were being commanded.

It is unclear whether Securitate Director Iulian Vlad initiated or could have turned off the “terrorist” actions. What is clear is that he knew the details of the plan and could have told the revolutionaries and military about them. He did not. That he knew of the existence of the “terrorists” is clear: he told the Deputy Foreign Minister to be careful as the Securitate Directorate Five officers at the MAE would “wipe them out.” He yelled at the Securitate officers arrested in the CC building. Per Army General Ion Hortopan and a civilian (Sergiu Tanasescu), Vlad admonished them for not heeding his orders, but this may have just been a tactic to deceive the revolutionaries and cover up his role in directing them.

According to Hortopan, “Our troops arrested a number of terrorists who identified their Securitate unit (UM 672, 639, 0106, 0620) to which Securitate Director Vlad suggested they could be fanatics acting of their own accord.” What is significant here is that General Vlad realizes in this situation—when presented with the Securitate unit numbers from which the arrested terrorist suspects belonged—that he has few options. Elsewhere during these December days, he attempted to suggest that the shooting was the result of common criminals who had stolen arms, armed civilians who didn’t know how to shoot, or Hungarians.

The “terrorists” and the “Lupta de Rezistenta”

The “terrorists” were in fact the name given to a failed counterrevolution to save the Ceausescus that took the form of a guerrilla warfare “resistance struggle” (lupta de rezistenta). Its main and most important protagonists were culled from the Securitate.

Significantly, among the documents in the Revolution File, is a handwritten three-page “urgent message” dated 25 December from retired Securitate foreign intelligence officer Domitian Baltei to those overseeing the campaign against the “terrorists.” In it Baltei details the actions and locations of what he refers to as “the resisters,” in other words those involved in the lupta de rezistenta. He talks about the involvement of Securitate Directorate Five (Service for the Protection and Guarding of the Ceausescus) officers and reservists, the use of safe houses, and the secret Securitate telephone exchange where the Securitate intercepted and redirected phone calls. He used the term “resisters” interchangeably with the term “terrorists.” Baltei was no uninitiated neophyte, however. In the late 1960s he had overseen the creation of funding mechanisms for the “resisters” abroad and thus knew of the “lupta de rezistenta.”

The “lupta de rezistenta” was drawn up in the late 1960s initially to respond to an invasion and occupation of Romanian territory, in theory by NATO, but in actuality by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies. Over time the plan was adapted to counter a potential military coup or popular revolt. However, its authors could never have conceived of and prepared for a popular revolt in which the military defected from the regime to the side of the people, as happened in December 1989. Like other so-called “stay-behind forces,” the “lupta de rezistenta” aimed at causing panic, mayhem, and confusion, with the goal of slowing the enemy’s advance and preventing the “occupying” government from functioning normally. In its initial stages then, it did not imagine the seizing of military and political objectives, because even if it had forces to conquer such objectives it was unlikely to have enough forces to hold such objectives. It was a plan for a battle that could take weeks or months, yet the compressed timeline of what happened in December, and the capture and holding of the Ceausescus, forced them to speed up the timeline and types of actions they engaged in, to include infiltration efforts and ambushes. Notably, preparations for what happened after 22 December 1989, began in some cases back to before the XIVth PCR Congress in November, and especially in the days preceding the 22nd.

It was in southern Romania, from the border with non-Warsaw Pact member Yugoslavia through the mountains in the center of the country to the Black Sea, where much of the most intense action took place in December 1989. The focus on the televised images of the CC or TVR misses the fact that it was in places, out of the domestic and international media spotlight, like Resita and Hateg, where you had real battles. Significantly, antiaircraft units were a particular objective of interest for the “terrorists.” They were subject to radioelectronic warfare, to terrestrial shooting, and to a wave of disinformation phone calls and intercepts or blocking of their communications. Antiaircraft units were targeted because the “terrorists” needed to secure the airspace in these more vulnerable points (the Yugoslav border; the Black Sea) to evacuate or infiltrate forces, and if they rescued the Ceausescus, to spirit them out of the country.

Iliescu’s responsibility

Because the “terrorists” existed and fought on behalf of Ceausescu, Ion Iliescu is not guilty of the crimes the Indictment alleges. This will be an unpopular answer for many Romanians, but it is the truth found in the files. Iliescu’s mistakes tended to be more of what he did not do, rather than what he did—sins of omission, rather than sins of commission. He was reluctant to execute the Ceausescus, even though the evidence was accumulating that as long as the Ceausescus remained alive, the chaos and death would continue. As head of the CFSN and then as President, his willingness to grant amnesties and his unwillingness to hold the Securitate accountable contributed to the burying of the truth about December 1989. Iliescu was really a transitional figure and thus had he accepted that role and walked away from power in 1990, his reputation would be far better today. Romanians like to think of the post-1989 political evolution of the country—seven years of rule by the successors of the Romanian Communist Party—as unique. They don’t have to look far to see that Romania’s political evolution was not. In Bulgaria, with a short-lived exception in 1991-1992, political power was dominated by the Bulgarian Socialist Party, the successor to the Bulgarian Communist Party. In Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic held power until 2000. And unlike Milosevic, who refused to stand down when he lost an election, Iliescu relinquished power peacefully in 1996 (after losing an election) and again in 2004 (when his mandate had expired). And during his second term (2000-2004) Romania continued to progress toward EU and NATO membership, with the latter actually being achieved during Iliescu’s Presidency.

What is missing and what should Romanian youth know about December 1989

Unfortunately, the Revolution File is incomplete. For example, we have noticed that in the cases of Sibiu, Braila, and Resita, many volumes are missing. We are sure that there are volumes missing in the case of other places too. We have learned the hard way that many files from the Revolution File were sent back to local procuracies under the pretense that they “did not contain information relevant to the investigations.” In fact, those few files we have recovered from a local procuracy show exactly the opposite and that they appear to have been sent back to local procuracies to bury them. Although prosecutors have closed the file examining the events of 15-22 December 1989, these files probably need to be reopened to properly assess responsibility for the bloodshed in Timisoara and elsewhere. Just as the military prosecutors can’t be trusted in what they say about what happened after 22 December, we believe that they can’t be trusted completely about what happened before 22 December.

Young people should know that Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were not “victims” of the Revolution as Pitu has sought to suggest in relation to their trial and execution. They were responsible for the bloodshed and death, including after 22 December. Young Romanians need to know that they should be proud of how most Romanian citizens acted in December 1989. The Romanian Revolution of December 1989 should be seen as a heroic event that gained worldwide recognition.

The former Securitate has stolen the Revolution from Romanians, to make them believe foreign agents before and after 22 December played an important role, to believe that the events were more coup d’etat than popular revolt. Romanians need to reclaim the authenticity, spontaneity, and courage of the Revolution of December 1989 from the former Securitate.

PART II

Lack of progress in investigating the Revolution under Traian Băsescu

– Why do you think that during Traian Băsescu’s presidency no real progress was made in clarifying the events of December 1989?

–It wasn’t just Basescu’s presidency during which there was no real progress made in clarifying the events of December 1989. It was merely a continuation of what happened under Iliescu and Constantinescu and what would continue under Iohannis. From 1994, no institution of the Romanian state—especially not SRI or the Military Procuracy—had an interest in the truth about December 1989.

– What does the discussion between Laura Codruța Kovesi and Traian Băsescu reveal about Băsescu’s understanding of justice and the independence of investigations?

My interpretation of this famous incident from 9 September 2009 is that this was for show as the 20th anniversary of December 1989 approached. In Basescu’s populist manner, he made it look as if he was channeling public frustration and outrage against “the elites”—”the bureaucrats,” in this case the Prosecutor General—on camera. “Justice” was to blame, not Basescu. His twice-repeated phrase of “don’t confuse me with journalists” demonstrated a contempt for justice and the independence of investigations.

– How did the president’s attitude influence the relationship between Cotroceni and the General Prosecutor’s Office in the Revolution cases?

Despite what I said above, I don’t believe Basescu gave “indicatii pretioase” in the Revolution Case. Basescu didn’t tell Kovesi what to do, he just said “do it”—“resolve” the cases. He expected “Justice” to do what it always did in the Revolution File—which was cover up the truth.

– How do you interpret Băsescu’s temporary support for military prosecutor Dan Voinea and then his removal?

Dan Voinea’s dismissal by Basescu in March 2009 was based on a request from Kovesi in October 2008. Kovesi accused Voinea of “making mistakes that not even a novice would make” in the Revolution and Mineriade files. It was thus Kovesi who wanted Voinea to be gone, rather than Basescu, who merely signed off on Voinea’s dismissal.

– What can you tell us about Colonel Ion Baciu’s testimony that he knew Lt. Col. Voinea Dan because he worked in the State Security Department, criminal investigation division?

I have come to believe that Baciu was wrong when he referred to Dan Voinea in his deposition. He may have confused Voinea with another military prosecutor, possibly Mircea Levanovici, or Judge Coriolan Voinea. As far as I know, Dan Voinea did not work for the State Security Department, criminal investigation division.

– Do you believe that Băsescu truly sought to uncover the truth about the Revolution, or did he use the case for political purposes?

As I said above, Basescu, like those who came before him as president and those who came after him, was disinterested in the truth about December 1989. Basescu clearly has a Securitate background, but I don’t believe that is why the truth about December 1989 was not revealed during his presidency.

II. Dan Voinea, the Tismăneanu Report, and the construction of a false narrative

– What responsibility does Dan Voinea bear for the legal compromise of the Revolution files?

From what I have heard, Voinea was a terrible prosecutor. Sloppy and lazy enough to ask other people to write things for him. He may have become anti-communist, but he avoided the truth about the Securitate’s actions after 22 December in his investigations. Like any other Ceausescu era prosecutor, he knew the conclusion that the Securitate wanted to be drawn in any investigation. The role of the military procuracy was to confirm what the Securitate gave them. Moreover, Voinea has admitted that in December 1989 he personally released a terrorist suspect, a former colleague (Pana) from the unit in Dragasani where Voinea did his military service. He released Pana even though, like other terrorist suspects, Pana had the usual three layers of clothing (including a salopeta) and three identity cards.

– How did his error-ridden “investigations” come to form the basis of the chapter on December 1989 in the Tismăneanu Commission’s Final Report?

The Tismaneanu Commission’s Final Report was a rushed document, coming out 8 months after Tismaneanu was appointed Commission Chair. It looks as if the Revolution chapter was added at the last minute and was hurriedly written.

Apparently, Stelian Tanase wrote it. It includes 3 ½ pages verbatim from a 1996 chapter by Tismaneanu that is not cited. Tismaneanu says “what? You accuse me of plagiarizing my own work?” No, the issue is that in typical Romanian fashion, the author of the chapter chose to include the work of the Commission Chair, because the Commission Chair had given him the chapter to write. Tismaneanu will say, these were all collective decisions, and everyone had an equal role and everyone assumed the final product. However, one must be naïve if one actually thinks that the inclusion of 3 ½ pages of Tismaneanu’s work is not the result of typical patron-client relations in Romania. Moreover, Tismaneanu’s writings and understandings of December 1989 are very thin and he routinely repackages things he wrote in the 1990s, as if no one had come up with anything new since then and he is the authority on any political event over the past century. If the Final Report had been treated like what it was, a rushed first cut at recent Romanian history, that would have been one thing; but, instead, Tismaneanu treats it as if he were Moses coming down from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments, unerring and eternal. Only minimal “corrections” were made after the publication of the document.

– To what extent did the Report uncritically adopt the false narrative that the “terrorists” were an invention of Ion Iliescu?

An interview by Andrei Badin with Dan Voinea, in which Voinea denied the existence of the “terrorists,” served as the basis for that conclusion. It could have been anyone who conducted an interview with Dan Voinea. Just like how most of the Romanian media—and especially the so-called anticommunist intellectuals, “Basescu’s intellectuals”—just accept as truth what Catalin Ranco Pitu tells them, so it was with Dan Voinea. Voinea told them what they wanted to hear—there were no terrorists, Iliescu is guilty—and so they welcomed and promoted what Voinea said. These people believe that the idea that the “terrorists” existed is a “FSN-ist, Iliescu theory.” They fail to understand that the opposite of their theory is the former Securitate’s theory that the “securisti-teroristi” did not exist and the Securitate were scapegoated in December 1989. To begin with who is more credible? Iliescu and his associates? Or the former Securitate? These people do not understand that they are replicating the former Securitate’s theory. Tismaneanu likes to say that he doesn’t read what the Securitate says and thus he couldn’t be influenced by them, or he identifies the Securitate narrative solely with Pavel Corut’s discussion of “bubuli.” But like so many of his intellectual friends, he has not traced, as I have, the evolution of the former Securitate’s narrative and how it penetrated the anti-Iliescu media in the early 1990s and went mainstream.

– What facts did the Report ignore or distort in relation to the events of December 22–27?

Pretty much everything. It just took Voinea’s word as truth: that the “terrorists” didn’t exist and that they were “invented” by Iliescu and the CFSN.

– Why do you think the Commission’s chairman, Vladimir Tismăneanu, avoided confronting the declassified documents from the US, the UK, and Canada? What did those documents reveal?

He didn’t ignore them. Those documents had not been declassified and released yet when the Report was written, in 2006. They were only declassified and released in the 2010s. These documents reveal that the CIA, the State Department, and UK Foreign Affairs and Canadian intelligence believed in the existence of Securitate terrorists. Tismaneanu does ignore them now because he doesn’t want to know them, acknowledge them or analyze them, because they discredit his writings and the Final Report’s chapter on December 1989.

III. The Băsescu–Tismăneanu relationship and the symbolic manipulation of the “condemnation of communism”

– How do you explain the fact that Vladimir Tismăneanu constantly defended Traian Băsescu’s image, even after the CNSAS verdict?

Before Basescu named Tismaneanu to head the Commission, Tismaneanu was lukewarm about Basescu. But once Basescu named Tismaneanu, Tismaneanu became fiercely loyal. I mean, Tismaneanu says “When Basescu speaks, I don’t hear ‘Petrov’”—Basescu’s codename as an informer. To which my reaction is: of course, you don’t hear ‘Petrov,’ because you are in total denial and have supported Basescu in almost everything he has done over the past 19 years. Tismaneanu has built up a mythology—the exact kind of mythology he analyzes and accuses others of all the time—around Basescu. Of how Basescu was transformed and converted into this “anti-communist, anti-Securitate” true believer and how heroic Basescu was when he presented the Report to parliament on December 18, 2006—a date which Tismaneanu insists be marked in every year, although with each passing year he is able to get fewer and fewer clients to sing its praises.

One has to remember that Tismaneanu had lost many intellectual friends because of his book length interview with Ion Iliescu, while Iliescu was a sitting president, and their media tour on Marius Tuca’s show and elsewhere (2002-2004). Because Iliescu was still in office, this seemed like opportunism to many other anti-communist intellectuals. Tismaneanu was ostracized in the way that happens among Romanian intellectuals. He was so much ostracized that he would end up writing an op-ed for a year in Dan “Felix” Voiculescu’s Jurnalul National. Tismaneanu’s defense? It had not been proved legally yet that Felix had a Securitate past. One can still hear the laughter from Bucharest. Two years later he would be praising Basescu for revealing Voiculescu’s Securitate past, even though Basescu had accepted the support of Voiculescu’s party in the December 2004 elections.

Tismaneanu’s vulnerability in the wake of his book with sitting President Ion Iliescu made him a perfect mark for Traian Basescu. Basescu would be his savior, and indeed he was. Tismaneanu went from being isolated among Romanian intellectuals, to being the gatekeeper to inclusion on The Commission.

– What does the photo from the 2006 Police Academy ceremony, in which Băsescu appears alongside the former head of the Securitate, Iulian Vlad, reveal?

The photo, from 21 July 2006, in which Vlad stands one person behind and away from Basescu is very revealing. It shows just how unserious and insincere Basescu was about the Tismaneanu Commission and the condemnation of the Securitate. As President, Basescu could easily have insisted Vlad leave. He did not. He clearly did not see anything wrong with Vlad being at the ceremony and standing close to him. It sent the message that the former Securitate had nothing to fear, in practice, from the Tismaneanu Commission.

Tismaneanu has insisted that from April 2006 Basescu was “convinced of the necessity” of the Commission and that for Basescu “breaking with the communist past was inseparable from the breaking of the political, moral, and social vestiges of totalitarian despotism.” Tismaneanu so prized the Commission Chairmanship, which Basescu had given him, that it was necessary to build a myth about Basescu: the changed man who was convinced by the Commission’s amazing work to break with the past. If this was just a rhetorical, political act by Basescu then it would undermine the importance of the Commission and the Final Report, and consequently, Tismaneanu’s importance. Tismaneanu just ignored Basescu’s actual behavior and focused on Basescu’s rhetoric. Those were just words, not deeds. In actuality, the Commission had very little real impact—not unexpectedly, given the Basescu-Vlad photo. Needless to say, Tismaneanu has never addressed this, because it undermines the myth he created. To see the hypocrisy, imagine how Tismaneanu would have reacted if a similar photo of Vlad with Iliescu, Constantinescu, or Iohannis had surfaced.

– Could the Băsescu–Tismăneanu case be a “double game” in relation to the former Securitate – a rhetorical condemnation and a real continuity?

It isn’t Tismaneanu’s double game. Tismaneanu is genuinely anti-communist and anti-Securitate, although he strategically employs it, forgetting about it when it comes to allies, and activating it when it comes to opponents or critics.

Basescu, on the other hand, definitely played a double game. Others have played it since, but few as effectively as Basescu. As it was, had PM Tariceanu not awarded Marius Oprea ICCR in December 2005, I sincerely doubt there would have been a commission. The Commission was Basescu’s way of “one-upping” Tariceanu, with whom he was increasingly in conflict. Basescu was able to detract attention from his own Securitate past, by rhetorically criticizing communism and the Securitate. That may seem a contradiction, but for someone as much of a chameleon and cynic as Basescu, it made perfect sense. How better to distract from his own Securitate past than to rhetorically criticize the Securitate? And if people think Basescu’s connection to the Securitate was only during his student days, as they say in the United States, I have a bridge to sell you. There is enough evidence to believe that after his informer days, he worked for the local Constanta Securitate from 1979 to 1987, before becoming an undercover foreign intelligence officer (CIE) during his time in Anvers, Belgium, 1987 to 1989. In fact, the emphasis on his student days, is a good way to avoid the larger questions about his later connections. Moreover, he surrounded himself with and advanced in the early 1990s precisely because of his ties to former CIE officers.

– To what extent was the speech condemning communism on December 18, 2006, more of a political gesture than a moral one?

Tismaneanu always brings up how Iliescu called him a “scribbler” and condemned the report and how Vadim Tudor made a scandal in parliament when Basescu presented it, because of how they were presented in the Final Report. But Tismaneanu never recognizes what for Iliescu, Vadim Tudor, and others was the hypocrisy of precisely Basescu, who did well under communism and was through and through Securitate, condemning communism and the Securitate. They recognized Basescu’s speech for what it was: pure hypocrisy and window-dressing. They knew well that Basescu hadn’t changed, that for him this was all political theater. Only the convenient and selective blindness of Tismaneanu and others prevented them from seeing this and acknowledging it. That is why even today they can’t admit it. Because if they were to admit it, they would have to admit that Basescu tricked them or they themselves had been blind or opportunist. Far better to be honest: Basescu used them because it was politically convenient, but they effectively used Basescu to get a politician to formally condemn the old regime. But no, instead we get grandiose claims about how the Final Report was imperative because Romania was going to enter the European Union on 1 January 2007. Really? Hungary in 2004, and Bulgaria in 2007, both entered the European Union without any such commission or condemnation of the communist regime.

– How was the Final Report used as an instrument of legitimization and political capital for the Băsescu regime?

For Basescu it turned out to be a good bet. Many intellectuals “held their fire” and failed to criticize Basescu’s well-known corruption and penchant for extortion—which the anti-FSN press detailed in the 1990s, sometimes no doubt with SRI “intoxication” following the Iliescu-Roman split. But this did not mean the accusations were false. Basescu’s faults were already known while Basescu was mayor of Bucharest. I had one American academic tell me Basescu asked him straight out for a bribe during this time. Basescu wasn’t an authoritarian, but from what I have read and heard, he was a crook. Anybody who thinks, all those around Basescu were crooks, whether his brother Mircea, or his mistress Elena Udrea, but he was not, only fool themselves.

IV. The “Petrov” file and Băsescu’s links to the Securitate

– What impact did the 2019 court decision confirming Traian Băsescu’s collaboration with the Securitate have?

It merely confirmed what had long been known. It did not, however, address the more sensitive issues of Basescu’s relationship to the Constanta Securitate from 1979 to 1987, and his being an undercover CIE officer in Anvers from 1987 to 1989. I naively believed that by affirming Basescu’s informer status something good had been achieved; but it turns out it was just another example of the political use of the files. This was the “USL,” Iohannis payback against Basescu.

– How do you interpret the fact that the Fourth Directorate of Military Counterintelligence, with which he collaborated, was the same one involved in military surveillance and repression before 1989?

Anybody who thinks that the CI-sti were only interested in preventing recruitment by foreign intelligence services is naïve. They caused fear and they ruined the lives of soldiers. Speaking in general, I believe Dr. Mark Kramer, Director of the Cold War Studies Program at Harvard University, and who has special expertise in the study of the former Soviet Union, described military counter-intelligence officers as being some of the more “nasty” type of informers.

– How relevant is Băsescu’s professional biography (Navrom, Antwerp, Ministry of Transport) to understanding his relationship with the Securitate apparatus?

It is very important. You mention Ministry of Transport, thus after December 1989. It is well known that Basescu surrounded himself with and advanced politically because of his ties to the former Securitate, especially of CIE (see, for example, the case of Silvian Ionescu).

– What consequences does this collaboration have on the credibility of the Romanian state’s condemnation of communism?

The Final Report and the Romanian state’s condemnation of communism still have value, but nothing like its promoters want people to believe. Basescu’s actions and hypocrisy undermine its value.

– What was the role of protecting former Securitate officers in Băsescu’s entourage after 1989?

This seems to have been a practice of as we say, “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” PCR—pile, cunostiinte, si relatii—lasted well beyond December 1989. Who were those pile and cunostiinte in Basescu’s world—former Securitate officers, especially those in foreign intelligence (CIE/SIE).

V. Control over the public narrative

– How did the academic and media network formed around Tismăneanu and Băsescu influence the public representation of the Revolution?

Tismaneanu used his credibility in Western academia to legitimize Basescu. Like many others in the US and elsewhere, I believed Tismaneanu’s noble language about values for far longer than I should have. I had long decided that Tismaneanu knew very little about December 1989, but I still thought he was credible on other matters. I should have been suspicious of Tismaneanu when he published his book with Iliescu. I was skeptical when the English academic, Tom Gallagher, accused Tismaneanu of attempting to create patron-client networks inside and outside Romania, but he was exactly right. In truth, in the mid-2000s, most Western academics still believed anything that was not PSD and that claimed to be anti-communist was good and credible. Basescu shows how damaging such a narrative was. Those who came out in support of Basescu and wrote chapters in yet another Tismaneanu creation for a sitting president can’t be faulted; they simply did not know or question enough. Other Romanian intellectuals and some Western academics are far more sober today in their assessments of Basescu and Tismaneanu. The illusions are gone.

– Why was the debate about Băsescu’s collaboration with the Securitate avoided in Romanian and Western academic circles?

Tismaneanu’s influence and wishful thinking are among the notable factors. It is not true that it has been completely ignored. The Romanian-Canadian academic, Professor Lavinia Stan, has addressed the Basescu case and placed it in the larger issue of lustration at the Jena Cultures of History Forum in December 2-19. I encourage those interested to read that piece, which is available online.

– How much did this network contribute to blocking a real lustration in Romania?

I see it merely as a continuation of what came before it and what came after it—hopelessly political.

– What common interests linked the “anti-communist” intellectuals to the former president?

See the above discussion on the Commission and its Final Report.

VI. Moral and historical reassessment

– What should be revised today in the official interpretation of the Revolution and the years 2004–2014?

Most Romanians appear to recognize and have recognized the disjuncture between Basescu’s words and deeds. The illusions and propaganda about Basescu should end.

– How can the myth of Băsescu as a “reformist and anti-communist president” be deconstructed?

See the above discussion.

– Why do you think Romania failed to produce a truly independent commission for the truth about December 1989?

It has been in nobody’s interest. And as we have seen previous attempts have been hopelessly politicized. Moreover, the former Securitate are mafia-like. Fear and self-censorship thus have not died.

– What should be the role of the new generations of historians and journalists in correcting these falsifications?

Be an equal opportunity skeptic, especially regardless of the political orientation of the people and institutions being studied.

– What connection do you see between Băsescu’s past in the Securitate and the stagnation of the Revolution files?

As discussed above, ironically, I don’t think it had a meaningful effect, as demonstrated by the actions of other presidents without a Securitate past.

– How can public trust be restored in institutions that have been politically compromised in investigating the truth about 1989?

First, IRRD needs to be shut down. Unlike what many people think, its main problem is not its defense of Iliescu, but its defense of and unwillingness to challenge the former Securitate. There should be an incompatibility between serving on CNSAS—the institution charged with examining the files of the former Securitate—and any affiliation with SRI (including teaching at the SRI’s Intelligence Academy), the institutional successor the Securitate. This is a rather clear conflict of interest. The Revolution File should be taken away from the Military Procuracy and given to a new, independent body to study them and arrive at conclusions about them.