(purely personal views based on over two decades of prior research and publications)

see also my earlier http://atomic-temporary-3899751.wpcomstaging.com/a-czech-mate-for-watts-theory/

Dr. Larry L. Watts’ argument that the Soviet agents (KGB, GRU, etc.) posing as “tourists” were directly involved in the overthrow of Nicolae Ceausescu’s communist Romanian regime in December 1989 has parallels in the historiography of the collapse of communism elsewhere within the countries of the Warsaw Pact, most notably perhaps, the former Czechoslovakia. Watts never addresses if he believes Romania was part of a similar process that took place in other countries or whether it was unique in the events of the bloc in the fall of 1989–perhaps in part because of his emphasis on the uniquely (for the Warsaw Pact) antagonistic relationship between the Soviet Union and Nicolae Ceausescu’s Romania. A comparison of revisionism in the Czechoslovak and Romanian cases suggests interesting similarities.

I first explored the question of the similarity in the historiography of the Romanian and other cases in my Ph.D. dissertation from which I reproduce the fragment below.

http://atomic-temporary-3899751.wpcomstaging.com/rewriting-the-revolution-1997/

“Yalta-Malta” and the Theme of Foreign Intervention in the Timisoara Uprising

At an emergency CPEx meeting on the afternoon of 17 December 1989, Nicolae Ceausescu sought to make sense out of the news from Timisoara by attempting to fit it in with what had happened elsewhere in Eastern Europe thus far that fall:

Everything which has happened and is happening in Germany, in Czechoslovakia, and in Bulgaria now and in the past in Poland and Hungary are things organized by the Soviet Union with American and Western help. It is necessary to be very clear in this matter, what has happened in the last three countries–in the GDR, in Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria, were coups d’etat organized by the dregs of society with foreign help.[1]

Ceausescu was giving voice to what would later become known as the “Yalta-Malta” theory. Significantly, the idea that the Soviet Union and, to different degrees of complicity, the United States and the West, played a pivotal role in the December 1989 events pervades the vast majority of accounts about December 1989 in post-Ceausescu Romania, regardless of the part of the ideological spectrum from which they come.

The theory suggests that after having first been sold out to Stalin and the Soviet Union at Yalta, in early December 1989 American President George Bush sold Romania out to Mikhail Gorbachev during their summit in Malta. The convenient rhyme of the two sites of Romania’s alleged betrayal have become a shorthand for Romania’s fate at the hands of the Russians and other traditional enemies (especially the Hungarians and Jews). To be sure, similar versions of this theory have cropped up throughout post-communist Eastern Europe among those disappointed with the pace and character of change in their country since 1989.[2] The different versions share the belief that Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet KGB engineered the sudden, region-wide collapse of communism in 1989. Their successors in Russia have been able to maintain behind-the-scenes control in Eastern Europe in the post-communist era by means of hidden influence and the help of collaborators within those countries. “Yalta-Malta” has become the mantra of those who seem to have experienced Eastern Europe’s el desencanto most deeply.[3]

[1].. See the stenogram from the emergency CPEx meeting of 17 December 1989 in Mircea Bunea, Praf in ochi. Procesul celor 24-1-2. (Bucharest: Editura Scripta, 1994), 34.

[2].. Tina Rosenberg, The Haunted Land. Facing Europe’s Ghosts after Communism (New York: Random House, 1995), 109-117, 235. Rosenberg suggests the theory’s popularity in Poland and especially in the former Czechoslovakia.

[3].. Huntington discusses the concept of el desencanto (the characteristic disillusionment or disenchantment which sets in after the transition) in Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave. Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 255-256.

The Czech Case

As in the Romanian case, there was an important outside-in dynamic to revisionism in the former Czechoslovakia in 1990. Whereas in the Romanian case, it was largely revelations–often from Romanians–in the French media, in the Czechoslovak case, revelations–often from Czechs themselves–came from British media.

The initial salvo in the Czech case appears to have been Michael Simmons’ 23 February 1990 article in The Guardian entitled, “KGB–Prague Plot Claim.” Dr. Kieran Williams later clarified, however, how deeply compromised these early commissions to investigate the events of the Velvet Revolution–most notably, the circumstances surrounding the events of 17 November 1989–were (see http://english.360elib.com/datu/U/EM309205.pdf pp. 45-48, pp. 53-54), containing among their ranks, almost inevitably, collaborators of the communist-era Czechoslovak secret service, the StB. Most notably, when one reads the Simmons account, cited by the commission as coming from a “well-placed Czechoslovak source,” the outlined conspiracy leaves the impression that 1) the StB did not intentionally engage in violence to prevent the fall of the communist regime (rather it allegedly encouraged unrest to replace Milos Jakes), and 2) they were in control and prepared for the initial stages of what happened. Thus, the StB appears both clean AND competent, only being upended by circumstances beyond their control. One suspects that the commission’s “well-placed source” was someone connected to the old regime, and perhaps from the StB itself, and thus with a vested interest in demonstrating retrospectively that their actions were noble and clairvoyant.

By May 1990, the primary public sources of the revisionist KGB theory appear to have been former Prague communist party chief Miroslav Stepan and Milan Hulik, the head of the parliamentary commission investigated the events of November 1989 (note: free and fair parliamentary elections in Czechoslovakia were held only in June 1990). [From Jan Obrman of RFE/RL 6 July 1990, “November 17, 1989: Attempted Coup or the Start of a Popular Uprising?” reproduced in full at http://atomic-temporary-3899751.wpcomstaging.com/a-czech-mate-for-watts-theory/ ] It is interesting to note, that Stepan, who was awaiting trial at the time, gave his interview to a newspaper (Lidove Noviny) associated with the anti-communist Civic Forum that had been at the heart of the Velvet Revolution, thus suggesting in the Czechoslovak case something that is well-known from the Romanian case: the intermixture of revisionism, opposition, disappointment, skepticism, and the forces of a nascent media market where journalists were intent on reexamining the past and revealing its truths.

The culmination of the burgeoning revisionism was a documentary by the BBC’s John Simpson broadcast on 30 May 1990, as described below:

http://articles.latimes.com/print/1990-06-01/news/mn-156_1_secret-police

Czech Revolution: A Secret Police Plot? : Intrigue: The BBC says leaders of the KGB and its Prague counterpart engineered the uprising ending Communist rule.

June 01, 1990|From Associated Press

LONDON — The peaceful revolution that swept away Communist rule in Czechoslovakia six months ago was engineered jointly by leaders of the secret police in Moscow and Prague, the British Broadcasting Corp. has reported.

A BBC television documentary contends that secret police leaders in both the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia conspired to bring down the hard-line Communist leadership in Prague because it rejected Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s reforms in the Soviet Union.

The plotters planned for more reform-minded Communists to replace the hard-liners but miscalculated the depth of public desire for change, said John Simpson, the BBC foreign affairs editor.

The 50-minute news program, “Czech-Mate: Inside the Revolution,” was broadcast on BBC-TV late Wednesday.

According to the broadcast, Milan Hulik, an investigator for the Czechoslovak parliamentary commission probing the plot, said that is not yet known if the revolution was instigated by the Czechoslovak secret police or the Soviet KGB.

“But all the facts point to KGB connivance,” he said. “We cannot reach any conclusion other than that the whole affair had been given the blessing of the Soviet political leadership.”

The plotters on the Czechoslovak side are now under investigation and some are in prison, charged with misusing their positions as public officials, while a parliamentary inquiry into the plot continues, Simpson said.

(In Prague on Thursday, police chief major Pavel Hoffman said that secret police headquarters have been put under special protection after a heated debate by several dismissed agents ended up in personal threats.)

Simpson said the spark that ignited the Czechoslovak plot was the erroneous report of a death of a youthful demonstrator during an officially sanctioned march in Prague on Nov. 17. The demonstration was held to mark the 50th anniversary of the murder of a Prague student by Nazi troops in 1939.

The plotters believed that a death during the November commemoration “would provoke a hostile reaction,” Simpson said.

According to the BBC report, several thousand young demonstrators were lured into a narrow street leading to Wenceslas Square by Lt. Ludek Zivcak, a secret policeman who had infiltrated the student movement.

The documentary showed a photograph of Zivcak apparently urging the marchers to take the narrow street that had not been part of the original route of the demonstration.

Once in the street, marchers were hemmed in by police and brutally beaten. About 560 people were injured.

Zivcak fell to the ground, his body was covered with a blanket and an ambulance took the body away. The event sparked rumors that riot police had beaten to death a student named Martin Smid.

In the days that followed, people poured into Wenceslas Square in the heart of the capital to mourn the death. And the protests continued to grow.

Demonstrations continued even after the only two students named Martin Smid at Prague University were shown to be alive.

The protests finally brought about the downfall of hard-line President Gustav Husak’s government, the creation of Czechoslovakia’s first non-Communist government in 40 years and the election as president of playwright Vaclav Havel, the country’s best-known opposition figure.

Simpson said the chief plotters were the Czechoslovak secret police chief, Gen. Alois Lorenc; the KGB head in Prague, Gen. Teslenko (first name not given), and KGB deputy chairman Gen. Viktor Grushko.

He said the plotters monitored the Nov. 17 demonstration together in Prague and that Grushko returned to Moscow the next day.

The plotters’ candidate to replace Communist Party chief Milos Jakes was Zdenek Mlynar, who had been a leading figure in Alexander Dubcek’s doomed reform government in 1968.

Mlynar, a friend of Gorbachev when they were law school students together in Moscow, had been purged by his own Communist leaders in 1969.

But Mlynar did not want the job when it was proposed to him, the BBC said, and Havel and his non-Communist Civic Forum were ushered into power by popular acclaim.

The Romanian Case

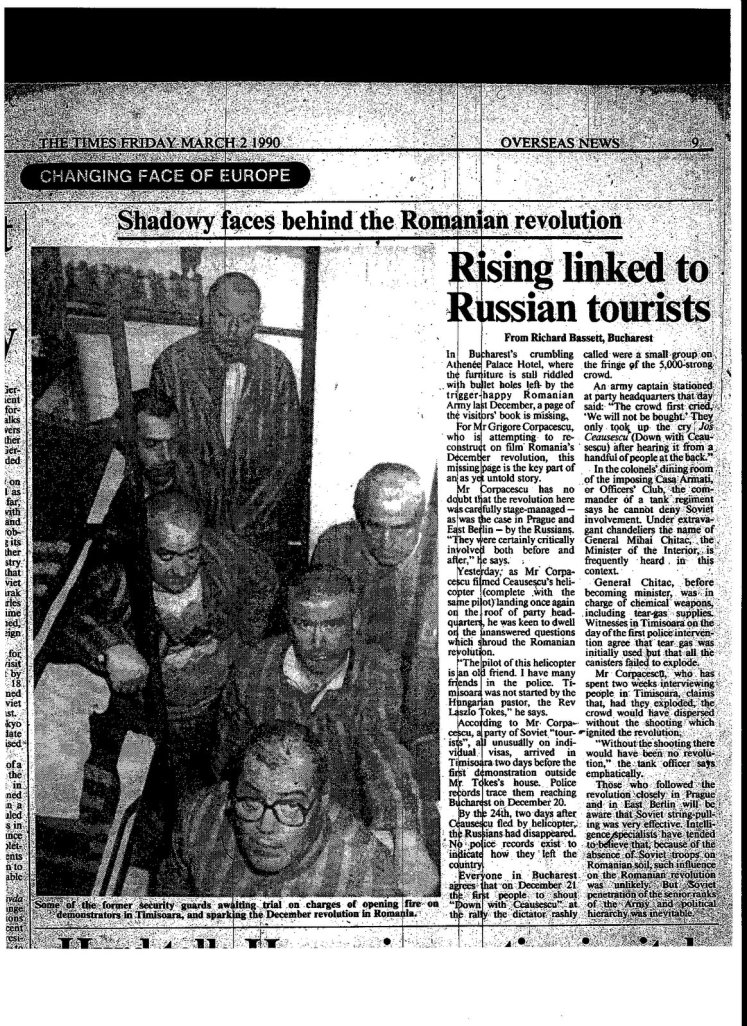

A week after the Michael Simmons story (23 February 1990) in The Guardian citing a “well-placed Czechoslovak source” on the alleged KGB hand behind the Velvet Revolution of November 1989, Richard Bassett published an article in The Times, citing a source who alleged the KGB was behind not just the revolutions in the GDR and Czechoslovakia, but in Romania too… (I assess it is unlikely, but cannot be completely discounted, that Bassett’s source was cognizant of the account in The Guardian…this was after all, five years before the advent of the Internet and it probably would have been difficult to get a recent copy of The Guardian in Bucharest at the time: if anyone knows differently, please correct me!)

from http://atomic-temporary-3899751.wpcomstaging.com/2014/11/29/schachmatt-strategie-einer-revolution-susanne-brandstatter-the-1989-romanian-revolution-as-geopolitical-parlor-game-brandstatters-checkmate-documentary-and-t/

THE 1989 ROMANIAN REVOLUTION AS GEOPOLITICAL PARLOR GAME: BRANDSTATTER’S “CHECKMATE” DOCUMENTARY AND THE LATEST WAVE IN A SEA OF REVISIONISM

By Richard Andrew Hall

(submitted for CIA PRB Clearance February 2005, cleared without redactions March 2005; printed as it was at the time without changes)

Disclaimer: This material has been reviewed by CIA. That review neither constitutes CIA authentication of information nor implies CIA endorsement of the author’s views.

from part 3 of this series

FOREIGN FORUM, ROMANIAN CONTEXT

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact first mention of “the tourists” and their alleged role in the Revolution, but it appears that although the source of the claim was Romanian, the publication was foreign. James F. Burke, whose name is unfortunately left off the well-researched and widely-consulted web document “The December 1989 Revolt and the Romanian Coup d‘etat,” alludes to the “Romanian filmmaker” who first made these allegations (Burke, 1994). The claims are contained in an article by Richard Bassett in the 2 March 1990 edition of “The Times (London).” According to Bassett,

“Mr. [Grigore] Corpacescu has no doubt that the revolution here was carefully stage-managed—as was the case in Prague and East Berlin—by the Russians…According to Mr. Corpacescu a party of Soviet ‘tourists,’ all usually on individual visas, arrived in Timisoara two days before the first demonstration outside Mr. [i.e. Pastor] Tokes’ house. Police records trace them reaching Bucharest on December 20. By the 24th, two days after Ceausescu fled by helicopter, the Russians had disappeared. No police records exist to indicate how they left the country. (“The Times (London),” 2 March 1990)

But Bassett’s interlocutor, Mr. Corpacescu, says some strange things. Bassett is not clear but it appears that Corpacescu suggests that the post-Revolution Interior Minister Mihai Chitac, who was involved in the Timisoara events as head of the army’s chemical troops, somehow purposely coaxed the demonstrations against the regime because the tear-gas cannisters his unit fired failed to explode—the failure somehow an intended outcome. But beyond this, Corpacescu, who is at the time of the article filming the recreation of Ceausescu’s flight on the 22nd—using the same helicopter and pilot involved in the actual event—makes the following curious statement:

“The pilot of this helicopter is an old friend. I have many friends in the police, Timisoara was not started by the Hungarian pastor, the Reverend Laszlo Tokes [i.e. it was carefully stage-managed…by the Russians].” (“The Times (London),” 2 March 1990)

The pilot of the helicopter was in fact Vasile Malutan, an officer of the Securitate’s V-a Directorate. What kind of a person would it have been at that time—and how credible could that person have been–who has the pilot as an old friend and “many friends in the police?” And it would have been one thing perhaps two months after the revolution to talk about the presence of foreign agents “observing” events in Timisoara, but to deny the spontaneity of the demonstrations and denigrate Tokes’ role at this juncture is highly suspicious. I have been unable to unearth additional information on Mr. Corpacescu, but his revelations just happen to serve his friends extremely well—particularly at at time when the prospect of trials and jail time, for participation in the repression in Timisoara and elsewhere during the Revolution, still faced many former Securitate and Militia [i.e. police] members.

…

Although revisionism in the Romanian case may have started in the British press, it was really in the French media that the revisionism played out:

from part 4 of the same series

The Evolution of the Initial French Accounts

The engine of the French revisionism of the first half of 1990 was probably the weekly “Le Point,”—although French Television (FR3) and other dailies and weeklies also played a role. In the 1 January 1990 edition of “Le Point,” Kosta Christitch wrote in an article entitled “Romania: Moscow’s Hidden Game,” that Ceausescu’s “fate had [not been determined in December] been sealed in Moscow less than a month earlier.” On New Year’s Day 1990, French Television broadcast the famous video which shows Ion Iliescu, Petre Roman, and Army General Nicolae Militaru talking on 22 December about what to name the(ir) group that had taken power, and in which Militaru claims that the “National Salvation Front has been in existence for six months already” (for details and a good discussion on this issue, see Ratesh, 1991, pp. 53-55, 81, 89-91). In the 8 January 1990 edition of “Le Point,” Radu Portocala entitled his article “Romania: The Hand of Moscow.” Portocala insinuated that Hungarian and Yugoslav media had intentionally exaggerated the number of casualties, particularly in the Timisoara repression [numbers which reached upwards of 10,000-12,000, when in actuality 73 died], while “at the same time, everything was put in motion to publicize that it wasn’t the [Romanian] Army that had opened fire [on the Timisoara demonstrators], but the Securitate.” On 5 February 1990, Portocala returned with an article, “Romania: Troubling Facts,” and on 30 April 1990, Olivier Weber wrote a piece, “Romania: The Confiscated Revolution.”

However, as Ratesh states, “…a fully developed conspiracy theory would not come to light until late May 1990, when the French magazine ‘Le Point’ carried a long and sensational article purporting to unveil the truth about the uprising” (Ratesh, 1991, pp. 81-82). The article, “Romania: Revelations of a Plot. The Five Acts of a Manipulation,” by Weber and Portocala, continued the themes that the authors had developed in their aforementioned articles, that Ceausescu’s overthrow was in fact a coup and that the communist bloc media had distorted information about what was happening inside Romania in order to propel Ceausescu’s fall. But it also included two new generally new themes, insinuating that foreign agents on the ground in Timisoara had had some role in the protests there—thereby undercutting the “spontaneity” of the Revolution—and that there had been no genuine “terrorists,” only “false terrorists,” part of a scenario for legitimating the coup d’etat. It was these newer themes that particularly became the focus of the Romanian media, and that prompted the most controversy.

It is difficult to overestimate the long shadow of the 21 May “Le Point” expose over the historiography of the Revolution. Translated by “Expres,” “Nu (Cluj),” and other key opposition publications in May and June 1990, it seemed to crystallize and explain all the doubts Romanians had about the December events—further confirmed, it seemed, by the manifestly unequal and unfair 20 May election results and then the miners’ rampage in Bucharest against demonstrators and the opposition press and parties during 13-15 June. The article’s trail shows up everywhere. American Romanianists Katherine Verdery and Gail Kligman who, in an article written in November 1990 sensibly inveighed against treating the Front, the former Securitate, and other groups as homogenous wholes operating in lock-step on behalf of Iliescu, discussed the Weber and Portocala as the centerpiece of the debate over December 1989 (Verdery and Kligman, 1992, pp. 118-122). However, although they questioned it, their summary of their own views on the events seemed to repeat many of the arguments of the account.

The Weber and Portocala account also shows up in the travel account of Dervla Murphy—although cited to “Romania Libera,” the description and details of her discussion make it clear the “Le Point” article is the source (Murphy 1995). Thus, Murphy floats the idea that perhaps the Reverend Tokes in Timisoara was in collusion with the coup plotters of the Front, and that “Soviet provocateurs and some Rumanian soldiers killed most of the victims—though everyone, in Rumania and abroad, was misled to believe the Securitate responsible.” It is telling, that although always somewhat skeptical of the notion of an external hand in sparking and fanning the Timisoara unrest, that in 1990, without having read the “Le Point” expose, but having followed English-language press and traveling for a month in Romania in July 1990 (I had first visited in July 1987), my own understanding was essentially along the same lines—how could it not be? My acceptance of the “staged war” theory would inevitably be strengthened in the following years by the accounts of noted Romanian emigres discussed below.

In Romania, Concern over the Unintended Consequences of the First Wave of French Revisionism

Certain key constituencies in Romania were not amused by the French revisionism in particular. In the wake of a demonstration in the cradle of the Revolution to mark nine months after the December events, Vasile Popovici of the Timisoara Society commented:

“The French press, in particular, with a penchant for excessive rationalization specific to the French, has attempted to accredit the idea of a KGB-CIA scenario, including in Timisoara. This fantasy variant demonstrates that those who sustain it have no idea of the real course of events in Timisoara and cannot explain in any way how people went out three days in a row (17, 18, 19 [December]) to die on the streets (Ciobotea 1990, interview with Vasile Popovici, “Vinovati sint mortii? [The Dead are to Blame?], “Flacara,” no. 40, 3 October, p. 3).

It is notable that in the same interview, Popovici who was no friend of the Iliescu regime, denounced the “attacks emanating from anti-FSN [National Salvation Front] publications upon the image of the popular revolt in Timisoara” [emphasis in the original; he included, the anti-Iliescu weekly “Zig-Zag” in the discussion, for more details on “Zig-Zag”’s critical role, see Hall 2002; Mioc 2000). Popovici underlined that the revisionism started in the anti-FSN press, and only then was integrated by the FSN press.

Specifically in reference to Olivier Weber and Radu Portocala’s 21 May 1990 expose in “Le Point,” (Army) Major Mihai Floca and Captain Victor Stoica declared: “We do not question the good faith of the French journalists, although the idea promoted by them is remarkably convenient to those who are just dying to demonstrate that, in fact, the ‘terrorists’ did not exist (Major Mihai Floca and Captain Victor Stoica, “Unde sint teroristii? PE STRADA, PRINTRE NOI (I), “Armata Poporului, no. 24 (13 June 1990), p. 3).” As this and other articles by the authors make clear, the reference is to the former Securitate—specifically, journalist Angela Bacescu in “Zig-Zag” (for a discussion, see Hall 1999).

Nor was the source of a key statement in Weber and Portocala’s article suggesting a fictitious “staged war” with fictitious “terrorists”—“There needed to be victims in order to legitimate the new power in order to create [the image of] a mass revolution,” according to the source—credible (see Hall 1999, p. 540 n. 90). Its source was former Navy Captain Nicolae Radu, a virulently anti-Semitic interloper and mercenary, who would become a regular in the former Securitate’s mouthpiece, “Europa,” in 1991, alleging all sorts of conspiracies about December 1989 that inevitably bestowed a primary role on Romanian Jewry and the MOSSAD. If Nicolae Radu’s claim about a “fictitious war with fictious terrorists,” sounds familiar from earlier parts of this series, it is: see, for example, the discussions of Dominique Fonveille (Part 2) and Ion Mihai Pacepa (Part 3).

As the above-cited observation by Floca and Stoica demonstrates, even if initially independent, streams French sensationalism and Securitate-inspired revisionism ended up converging and intermingling—a historical accident that redounded decidedly to the benefit of the latter. This was not only the case with the “terrorists,” but also with the issue of alleged “foreign agents” on the ground in Timisoara and their alleged role in the uprising. It is undoubted, has been reported, and has been admitted publicly that at one point or another, particularly in monitoring regime treatment of the Hungarian Pastor Laszlo Tokes, around whom the uprising broke out, that embassy and consulate personnel from the Yugoslavia (which has a consulate in Timisoara), United States, Japan, and other countries (likely to include Hungary, the UK etc.) appeared in Timisoara during these events. It would be naïve to believe that there were no intelligence personnel among those at the scene among these countries’ representatives. Of course, monitoring unfolding events is one thing, fomenting an uprising or monitoring the progress of a manufactured uprising by the countries for which they worked, quite another.

It is clearly the latter scenarios that foreign and domestic revisionists have alleged about Ceausescu’s overthrow. There are glaring contradictions in the logic of these revisionist accounts on this score, however. For example, accounts of the first Franco-German revisionist wave allege that the Hungarian and Yugoslav media intentionally inflated the casualty counts in Romania to move the coup forward by fueling anger at the Ceausescu regime. In doing so, we are told, these communist services were likely doing the bidding or aiding the effort of the Soviet-backed coup plotters, and thus of the Gorbachev leadership. In their 21 May 1990 expose, Weber and Portocala mention the presence of “Soviet observers” in Timisoara since at least 16 December 1989, when the demonstrations really began to take shape. They cite Tanjug, the Yugoslav news agency, as the source of this claim. Since this claim was first mentioned in the 1 January 1990 “Le Point” article by Kosta Cristitich, I can only surmise that the Tanjug claim was published sometime during the last week of December 1989. (I have been unable to find this reference in FBIS, which translated many Tanjug dispatches at the time, but I have no reason to doubt that this is what Tanjug related. It is therefore unclear who Tanjug heard this claim from—a fact which as we saw in the case of Mr. Corpasescu in Part 3 is important, since the claim could reflect disinformation or rumor.) A similar claim turns up in Andrei Codrescu’s book, The Hole in the Flag, in which he maintains that during the first week of January 1990, a Soviet journalist drinking-buddy for that night told Codrescu that he had been in Timisoara and that there in fact had been “a dozen TASS [Soviet news agency] correspondents” in Timisoara since 10 December 1989 (Codrescu, 1990, p. 171).

In essence, we are thus asked to believe that the exact media personnel who were behind a disinformation campaign to exaggerate the death toll in Romania and aid the Soviet-engineered coup, nonchalantly publicized the role of the Soviets in the uprising in Timisoara. This does not make a lot of sense, does it? Moreover, the presence of unhindered “Soviet observers” in Timisoara from 16 December—to say nothing, of the Codrescu claim, of “a dozen TASS correspondents” in Timisoara from the 10th—does not seem realistic. To begin with, Tokes only announced to his congregation on 10 December that the regime was probably going to deliver on their long-existing threat of evicting him on 15 December—meaning that either the “TASS correspondents” would have had to have had advance information of Tokes’ announcement or a certain amount of good luck/clairvoyance. Given the well-documented difficulties all journalists experienced in late 1989 in trying to get into the country, especially following the upheaval elsewhere in the bloc, it is hard to believe these “ dozen TASS correspondents” would have received visas into the country, presenting themselves as such—they certainly did not do much reporting from Timisoara, as like other news associations it was only on the 23rd that a Soviet journalist filed a report from there.* Moreover, it is significant that on the morning of 11 December 1989, Budapest’s Domestic [Radio] Service announced that the day before three staff members of the ruling party daily “Nepszabadsag” were banned for five years for attempting to approach Tokes’ residence—their film and tape recordings were also predictably confiscated (FBIS, 11 December 1989, and “New York Times,” 12 December 1989). So, how then is it, that the Hungarian correspondents were expelled, but the “a dozen TASS correspondents”—apparently somehow keeping well out of sight, and feeling no compunction to write on the topic of the Hungarian correspondents—were allowed to stay?

*Indeed, there appear to be no TASS dispatches from Timisoara throughout this period. According to FBIS translations, there appear to have been 3 TASS correspondents in Romania, in addition to one from “Izvestiya” and one from “Pravda,” all of whom reported during these days from Bucharest. A fourth TASS correspondent reported from Timisoara on 23 December, after the flight of the Ceausescus, and when most foreign reporters were able to enter Timisoara for the first time. Once again, according to FBIS translations, during the events of 15-22 December, TASS correspondents in Bucharest had to rely on other news services and sources in Bucharest to find out what was happening in Timisoara.

SOURCES

“Armata Poporului,” 1990.

Brown, J. F., 2001, The Grooves of Change: Eastern Europe at the Dawning of a New Millenium (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Budapest Domestic Service, 11 December 1989, in FBIS, 12 December 1989.

Calinescu, M. and Tismaneanu, V., 1991, “The 1989 Revolution and Romania’s Future,” “Problems of Communism,” Vol. 40, No. 1 (April), pp. 42-59.

Castex, M., 1990. Un Mensonge Grosse Comme Le Siecle (Paris: A. Michel).

Codrescu, A., 1991. The Hole in the Flag. A Romanian Exile’s Story of Return and Revolution (New York: William Morrow and Company).

Codrescu, A., 2002. “Codrescu Cogitates on Communism,” American Library Association Midwinter Meeting 18-23 January 2002, New Orleans, at http://www.ala.org.

“Flacara,” 1990, 1991.

Gabanyi, A.U., 1990. Die Unwollendete Revolution, (Munich: Serie-Piper).

Hall, R. A. 1997, “Rewriting the Revolution: Authoritarian Regime-State Relations and the Triumph of Securitate Revisionism in Post-Ceausescu Romania,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Indiana University).

Hall, R. A., 1999, “The Uses of Absurdity: The Staged War Theory and the Romanian Revolution of December 1989,” in “East European Politics and Societies,” Vol. 13, no.3, pp. 501-542.

Hall, R. A., 2002, “Part 1: The Many Zig-Zags of Gheorghe Ionescu Olbojan,” “The Securitate Roots of a Modern Romanian Fairy Tale: The Press, the Former Securitate, and the Historiography of December 1989,” Radio Free Europe “East European Perspectives,” Vol. 4, no 7.

“Jurnalul National (online),” 2004, 2005.

“Le Point (Paris),” 1990.

Mioc, M., 2000. “Ion Cristoiu, virful de lance al campaniei de falsificare a istoriei revolutiei” at http://www.timisoara.com/newmioc/51.htm.

Murphy, D., 1995, Transylvania and Beyond. A Travel Memoir (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Books).

“Neue Zurcher Zeitung,” 1999, (English edition) at http://www.nzz.de.

“New York Times,” 1989.

Ratesh, N. 1991, Romania: The Entangled Revolution, (New York: Praeger).

Shafir, M., 1990, “Preparing for the Future by Revising the Past,” Radio Free Europe’s “Report on Eastern Europe,” Vol. 1, No. 41, (12 October), pp. 29-42.

Stokes, G., 1993, The Walls Came Tumbling Down: The Collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe, (New York: Oxford University Press).

Verdery K. and Kligman G., 1992, “Romania after Ceausescu: Post-Communist Communism?” in Banac, I (ed.)., Eastern Europe in Revolution (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), pp. 117-147.

“Zig-Zag,” 1990.

(for a summary advocacy of both the Czech and Romanian revisionism, several years later, see John Simpson’s “How the KGB Freed Europe,” in the 5 November 1994 edition of The Spectator (UK), http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/5th-november-1994/11/how-the-kgb-freed-europe

Five years after the Berlin Wall came down,

John Simpson reveals who really caused the

overthrow of East Europe’s dictators

Berlin MOST HISTORIANS, and most journal- ists, instinctively distrust conspiracy theo- ries. They know that reality does not work so tidily: that entropy and Sod’s law are the most satisfactory explanations for most events. The instinctive assumption that behind every great event there must be a group of politically motivated conspirators doing the bidding of some great power is not one that sensible, rational people make.

Now that the fifth anniversary of the col- lapse of the Berlin Wall is upon us, there is a welter of television specials and special newspaper articles about the domino effect of 1989: how Hungary opened its borders with Austria, allowing East Germans to flock through the gap in their hundreds of thousands; how the government in East Berlin opened the crossings into West Berlin without meaning to on 9 November; how, eight days later, a peaceful demon- stration in Prague was met with violence by the Czechoslovak authorities and the resulting anger brought down the govern- ment; how, on 21 December, crowds in the main square in Bucharest forced President Ceausescu of Rumania to flee.

The pattern is clear enough; what scope could there be for conspiracy? And yet there is strong evidence that the secret police in East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Rumania worked with the KGB, which ‘Room service? Send up someone to pay my bill, please.’ supported Mikhail Gorbachev’s reformist approach, to bring down the old, conserva- tive leaders in these three countries and replace them with glasnost- and perestroi- ka-friendly regimes which would co-oper- ate with the new Soviet Union. The plan succeeded in the first objective and failed in the second: the old guard was indeed swept away, but only in Rumania did a reformist communist government come to power; and soon, anyway, Marxism-Lenin- ism had evaporated in Russia itself.

I first heard about it all in .May 1990, from a Czech dissident who was shortly to return to a senior official position in Prague. We had met at the Chelsea Arts Club and, at her insistence, were sitting in the garden so that no one would overhear us. Soon her story broke down my reserves of politeness. ‘Listen,’ I said, ‘I hate con- spiracy theories. I simply don’t believe a word of any of this.’ The very suggestion that the peaceful revolution in Czechoslo- vakia, the most moving and impressive event I had ever witnessed, might have been organised by the Czechoslovak secret police, the StB, with the KGB’s help, offended every principle I had. ‘I don’t blame you,’ said the woman. `Maybe, though, you should take a look at this.’

She handed me a sheaf of photocopies: it was the report of a ten-man parliamentary commission set up by President Vaclav Havel to look into the circumstances of the demonstration on 17 November 1989, the key moment of the Prague revolution. That evening a student was said to have been killed by the police, and although it turned out later to have been untrue, there was such anger among ordinary Czechs and Slovaks that they came out onto the streets in vast numbers and eventually forced the collapse of the old regime. I leafed through the report: there were interviews with virtu- ally everyone involved, including several with men of the StB who had taken part in the conspiracy. At the end was the summa- ry by one of the most senior figures on the commission, Dr Milan Hulik:

There is no doubt that the leading personali- ty of the whole operation … was General Lorene [the head of the StB] … The con- tacts between Lorenc and KGB officials which have been discovered couldn’t, in my opinion, point to any other conclusion than KGB connivance in the whole action .

The man who was supposed to have been killed gave evidence to the commission; he was, in fact, a young StB lieutenant, Ludek Zifcak, who pretended he had been struck over the head by a police baton. Someone covered him with a blanket, and his body was taken away in an unmarked ambu- lance. The news that someone had been killed by the police created a mood of implacable anger in the country. It was 50 years to the day since the German army, entering Prague, had shot dead a student who had demonstrated against them. The symbolism was overwhelming, and within a few days the old communist regime, truth- fully but pointlessly protesting its inno- cence of Zifcak’s ‘death’, simply evaporated. The plot had worked perfectly; the trouble was, no one had the slightest interest in reformist communism any more. Vaclav Havel and his Civic Forum were swept to power on an immense tide of pop- ular enthusiasm.

It would be a mistake to think that under the Soviet system the secret police was nec- essarily against political change. Yuri Andropov, as Chairman of the KGB in the 1970s, realised the terrible condition of the Soviet economy and the need to do some- thing radical about it. When he succeeded Brezhnev as head of the Soviet Communist Party in November 1982, he was too ill, and died too soon, to achieve anything; but he made sure that his protégé, Mikhail Gor- bachev, would be a contender for the top job. After Chernenko’s brief reign ended in March 1985, Gorbachev duly took over. The plans which Andropov had first formu- lated as head of the KGB were put into practice; and the KGB supported them.

It wasn’t the first time the Russian secret police had espoused ideas which were more radical than those of the established sys- tem; in the 1880s and 1890s, the head of the Tsarist secret police in Moscow, Colonel Zubatov, decided that the only way to protect the power of the throne was to set up unions for the working class which would compete for support with those run by genuine socialists. In 1902, thousands of workers appeared at the Kremlin bare- headed and kneeling and chanting, ‘God save the Tsar,’ But the mood of the author- ities changed; and when Father Gapon, a secret police agent, led a crowd of support- ers of the Zubatov unions to the Winter Palace in St Petersburg on 9 January 1905, the Cossacks shot them down. It was the start of the 1905 revolution, and of the eventual destruction of Tsarism.

In November 1989, then, the KGB played an active part in the overthrow of the hard-line, anti-reformist government in Czechoslovakia. In Rumania a month later, it is now abundantly clear that the unsavoury President Ceausescu was also the victim of a conspiracy between a pro- Soviet faction within the military and the security police on the one hand, and reform-minded communist politicians on the other. The vast crowd which on 21 December 1989, in full view of the live tele- vision cameras, booed Ceausescu in the square in front of the Central Committee building was carefully organised by the Securitate. As the viewers watched Ceaus- escu’s marvellously comical amazement at being given the bird by the huge number of people assembled before him, the chief of his personal bodyguard walked up behind him and said audibly into his microphone, `They’re getting in.’

They weren’t, and it wasn’t until the next day that the crowd broke into the Central Committee building and,Ceausescu had to escape by helicopter from the roof. But the television coverage had alerted people all over the country that the revolution was beginning. Nothing could stop it. Once again, the conspiracy had been successful and an anti-Gorbachev hardliner had been eased out. The new President, Ion Iliescu, was ideal material for the new Eastern Europe Mikhail Gorbachev hoped to cre- ate: flexible yet a faithful communist, pleas- ant-looking, unknown outside Rumania, capable of being elected in a vote that was more or less genuine; though it was already becoming clear that the overall plan, by which a more democratic Soviet Union would surround itself with popularly elect- ed governments favourable to Moscow, would come to nothing.

As for the event which began the revolu- tionary chain, the collapse of the Berlin Wall, that was brought about by a more complex set of circumstances. Here too there are signs of a conspiracy, though they are harder to trace. Senior figures in the East German Communist Party, the SED, knew very well that Gorbachev wanted them to get rid of the ultra-conservative Erich Honecker, even though Gorbachev himself was unwilling to give them their instructions directly. Marcus Wolf, the for- mer leader of the espionage branch of the Stasi, the security ministry, was in close contact with the KGB and knew perfectly well what was expected of them. Wolf was the model for John Le Carre’s East Ger- man intelligence chief in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, and perhaps also for his anti-hero, Karla. Having fallen out with Honecker, he had resigned from the Stasi in 1986, and had lived in retirement ever since. He seems to have been the link between the KGB and the anti-Honecker members of the Politburo.

Honecker was duly deposed in October, and the reformists took power, Thus far the plan had worked. But the new leader- ship had no clearer idea than the old one how to cope with the demonstrations demanding more open government and the right to travel freely to the West. At the Politburo meeting on 9 November it was decided to allow everyone to apply for an exit visa without having to state a reason. No one there foresaw the effect this would have. That evening the Politburo spokesman, Giinter Schabowski, walked into a news conference in East Berlin thor- oughly confused, with his papers in com- plete disorder. It was only as the news conference was drawing to an end that he found the document with the details of the Politburo decision, right at the bottom of the pile. He read it out hesitantly. When he had finished, someone asked when people would be able to apply for the new visas. Forgetting that the Politburo had decided that the process would begin the following morning, Schabowski said, `Unverziiglich: immediately. Someone asked him what that meant. Tired, confused by the shouted questions, blinking in the bright camera lights, Schabowski blurted out the words that brought the Berlin Wall down and led to the collapse of Marxism-Leninism throughout Europe. ‘It just means straight- away,’ he said. The news conference was broadcast at 7.30 that evening. Within nun” utes people were heading for the crossing- points in the Wall to see if it were true. At several places the VoPo guards, not having any orders about it, let the crowds through. It was all over. In East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Rumania, the secret police began the pro- cess of reform and revolution. But conspir- ators usually get more than they bargain for. As in Russia in 1905, the revolutions took on a life of their own; and in the end the plotters were swept away, as well as those they had plotted against.

John Simpson is an associate editor of The Spectator and foreign affairs editor of the BBC.)

—

The similarities between the Romanian** and Czechoslovak cases are then pretty clear. The initial sources of the revisionism had a vested, if not always obvious or publicly identified, interest in an account that absolved or even extolled the role of the domestic security services during the momentous events of late 1989. This intersected with the market-driven forces and journalistic culture of local, but also international media, looking for a sensationalist scoop and an advantage against competitors, with a readership at the time still interested in what had then only recently transpired. It is perhaps ironic, that precisely because the opposition, anti-communist media of the time was the most open to journalistic inquiry, that the revisionism alleging a Soviet hand, found its early home in these countries in that section of the media–although other potential factors cannot be totally discounted.

**In the Romanian case, I have outlined such arguments about the confluence of sources on several occasions, especially here: http://atomic-temporary-3899751.wpcomstaging.com/the-uses-of-absurdity-romania-1989-1999/

Leave a Reply