The Revolution File vs. Military Prosecutor Cătălin Ranco Pițu: “Every Army structure after January 1990 concluded that the terrorists did not exist” by Roland O. Thomasson (aka Richard Andrew Hall)[1]

Former military prosecutor General Cătălin Ranco Pițu has repeatedly made claims to Romanian media about the “after action reports” of the Defense Ministry (M.Ap.N.) that analyzed what soldiers experienced in December 1989.[2] Pițu maintains that these reports concluded that the “terrorists”—as presumed loyalists fighting on behalf of Nicolae Ceausescu were called at the time—did not exist. Pițu leaves little room for misinterpreting his accusation. He specifies that after January 1990, “every Defense Ministry structure” “without exception” came to this conclusion. He lists the structures: the air force (Aviaţie); the navy (Marină); territorial anti-aircraft defense command (Comandamentul de Apărare Antiaeriană a Teritoriului or CAAT); the infantry and tank command (Infanterie și Tancuri). He has proclaimed these analyses “fantastic” and “phenomenal.” He is thus unambiguous about the documents to which he refers and his conclusions.

Because Pițu is so specific in his claims—they also appear in the 2022 Indictment (Rechizitoriul) and in his book, Ruperea blestemului (2024, Editura Litera)—anyone who has access to the Revolution File can verify their authenticity. My colleague Andrei Ursu and I have a copy of the Revolution File. We thus have been able to study for ourselves the documents Pițu invokes. The “every MApN structure” argument is based primarily on documents that appear in the file entitled “Dosar revoluție nou.” This file contains many MApN documents that were declassified in 2017/2018 by the MApN Archive in Pitești. The after-action reports drafted by the MApN structures after January 1990 show that Pițu’s statements about the contents and conclusions of these documents are false. Instead of showing that these structures concluded that the terrorists did not exist, the documents show that these structures presented the terrorists as real.

Why does this matter?[3] It matters because it is a simple litmus test on the prosecutor’s ability to tell the truth about December 1989 and thus the validity of the Indictment itself, which covers the killing and wounding of thousands of victims. Such a blatantly false statement about the after-action reports should raise questions about the credibility of the rest of his case.

Revolution Research and the Problem of Selective Skepticism

Researchers of the Romanian Revolution have not always applied equal skepticism to the sources they have used and have not always included key voices who disagree with their favored sources. For example, Peter Siani-Davies takes the declarations of Valentin Gabrielescu (PNȚCD), the opposition head of the second Senatorial commission to investigate December 1989, at face value. Siani-Davies quotes Gabrielescu as talking about “imaginary terrorists” and telling the British Daily Telegraph on 12 December 1994:

As well as the army and the police, thousands of civilians were armed, and under the stress of false rumours and false dangers from inside and outside. Everyone shot at everyone else. Everybody was a “terrorist.” It was chaos. Everybody had a weapon in his hands. The army shot about five million rounds and the population as many as they could lay their hands upon—at first out of joy, then against the “terrorists.” Then because they were drunk.[4]

Siani-Davies discusses Gabrielescu in the context of the earlier Sergiu Nicolaescu Senatorial (PDSR) report, but he makes no mention of the Separate Opinion of Adrian Popescu-Necșești (like Gabrielescu, also opposition, but PNL-CD) appended to his report. I interviewed Gabrielescu at his apartment in June 1994, and although I found him affable, I also found him evasive and strategically calculating in discussing the Securitate. In June 1997, after reading an article about Popescu-Necșești’s Separate Opinion,[5] I interviewed the latter at his apartment. Popescu-Necșești not only presented a well-documented and reasoned study,[6] but had personal experience with “terrorists” in his bloc, which was located not far from the CC building. Popescu-Necșești believed firmly that the “terrorists” existed and that they were from the Interior Ministry (Securitate).

Researchers have seemingly exercised even less skepticism when examining the claims of former military prosecutor General Dan Voinea.[7] For example, Raluca Grosescu and Raluca Ursachi reduce the narrative of the “terrorist” threat to propaganda by Ion Iliescu’s National Salvation Front and analyze its “use” as serving Iliescu and the Front’s political interests.[8] Nowhere do Grosescu and Ursachi seem to question Dan Voinea’s narrative and whether it serves any political or institutional interests.[9] Yet Dan Voinea is not the only military prosecutor to have investigated December 1989 and talked publicly about it. Grosescu and Ursachi ignore two critical volumes by former chief military prosecutor General Ioan Dan, who had earlier been Dan Voinea’s boss.[10] Ioan Dan believes that the “terrorists” existed and that they were from the Securitate, and offered detailed documentary evidence in his books.[11] Significantly, Ioan Dan was ousted from the Military Procuracy after his 22 December 1993 intervention on national television (TVR) in which he suggested the role of the Interior Ministry before and after 22 December 1989.[12]

Pițu’s Media Tour and the “Every Defense Ministry Structure…” Narrative

Since retiring in March 2023, Pițu has been a constant presence on multiple platforms and media outlets across the Romanian political spectrum. He has rarely been challenged and tested in these interviews. Most interviewers simply take at face value what the former prosecutor tells them.

Pițu has been remarkably consistent in what he has told interviewers over the past three years. In May 2023, he told Ion Cristoiu:

every Army structure—Aviation, Anti-aircraft Defense, Infantry, Tanks, Navy—…structures…prepared their own very thorough analyses [i.e. after-action reports] after January 1990 about what happened hour by hour during the Revolution…their conclusions are phenomenal…EACH AND EVERY MATERIAL INDEPENDENTLY SHOWS THAT THE TERRORISTS [COUNTERREVOLUTIONARY CEAUSESCU LOYALISTS] DID NOT EXIST…[emphasis added][13]

In December 2023, Pițu told Timișoara journalist Melania Cincea:

Every Army structure—Infantry, Aviation, Anti-aircraft Defense, Navy etc.—performed their own analysis of the December 1989 phenomenon. And because, without exception, the conclusions drawn by the military specialists were that the terrorists did not exist and the diversion was done as I have told you, these documents were declassified. They were obtained via declassification only in 2017, 2018.[14]

Finally, in July 2025, he told Sergiu Silviu of Independent News:

Every MApN structure, that is to say Anti-aircraft Defense, Infantry, Tanks, Military Intelligence, Military Aviation. All these MApN documents, not DSS, not SRI, demonstrated that the ‘securist-terorist’ phenomenon was a phenomenon invented by the new politico-military power of Romania, with the goal of securing legitimacy and ensuring the impunity for some in MApN.[15]

There thus can be little room for doubt here about the documents Pițu is talking about or about his conclusions and accusations. He absolves the former Securitate and squarely blames the “new politico-military power” and theArmy for the bloodshed. Pițu’s statements are contradicted by the very MApN documents he invokes, as the following exposition from Dosarul Revoluție (The Revolution File) will demonstrate. Documents are from “Dosar revoluție nou” unless otherwise noted.

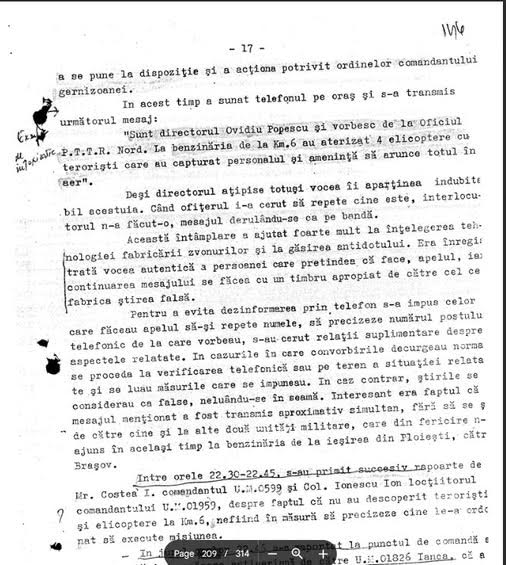

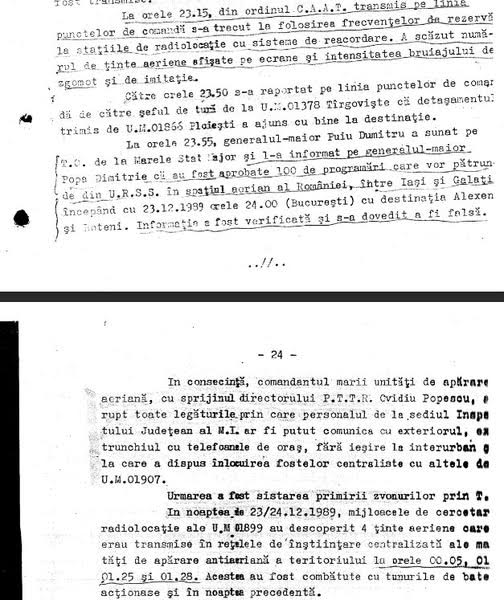

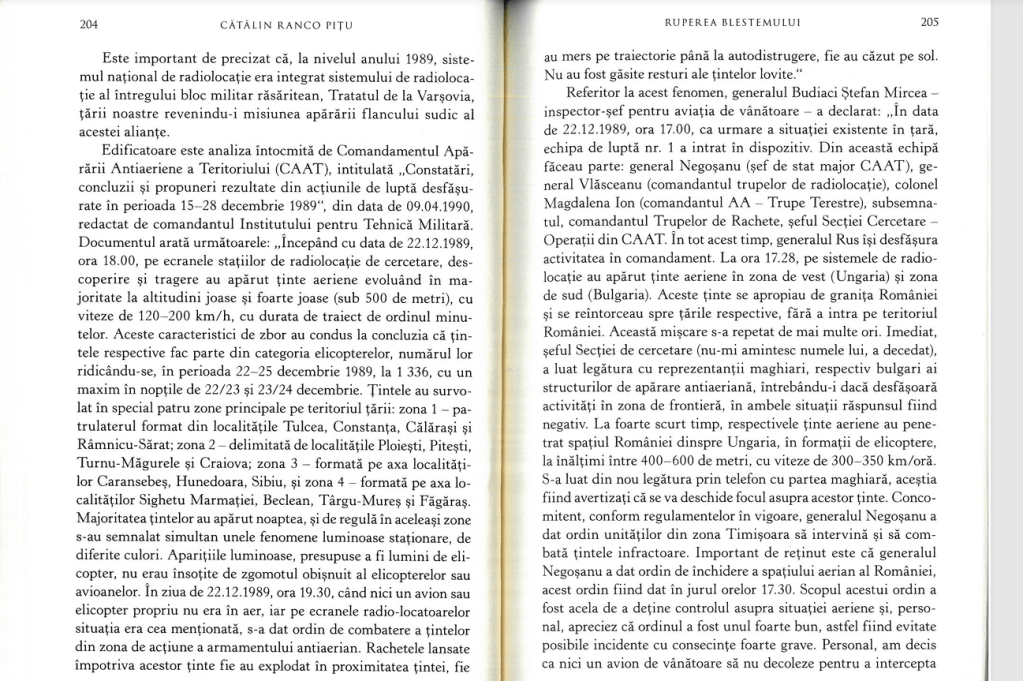

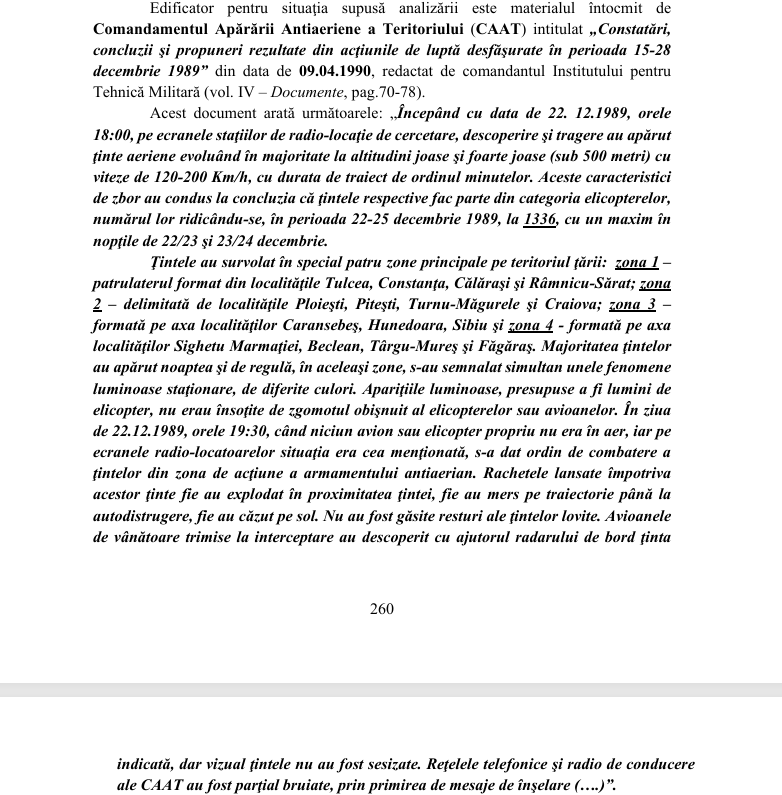

- On page 260 of the Indictment and page 205 of Ruperea blestemului, Pițu claims that a 9 April 1990 study by CAAT concludes that there were no terrorists. The prosecutor notes the line from the CAAT report that “no remains of a helicopter or plane that was shot at were found,” in order to buttress his argument that the terrorists were invented and did not exist. He neglects to quote passages that clearly show that in fact the CAAT specialists believed the terrorists existed and invoked multiple credible sources to prove it. For example, the specialists noted multiple eyewitnesses who sighted the terrorist helicopters, whose existence was corroborated by radar observations:

The multitude of aerial targets that appeared on radar screens can be divided according to their predominant characteristics:

–helicopters fitted for warfare or personnel transport, were sighted by many eyewitnesses during these days, the data furnished by the eyewitnesses being corroborated by the observations made on radar; these helicopters, or at least some of them had systems to create deception by jamming against aircraft radar, which prevented our planes from destroying them, the “enemy” helicopter creating false targets with their on-board radar.[16]

Pițu is thus incorrect when he claims that the 9 April 1990 CAAT study concluded that the terrorists did not exist.

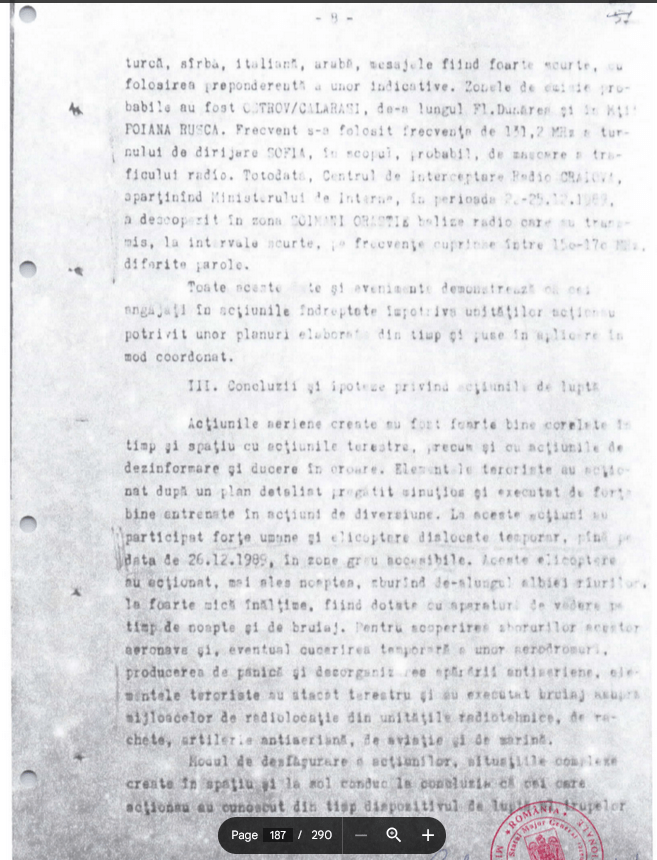

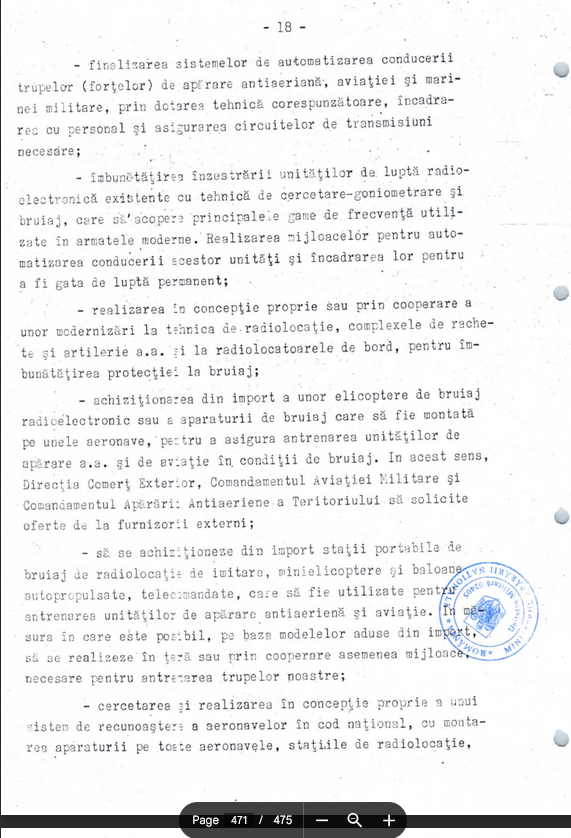

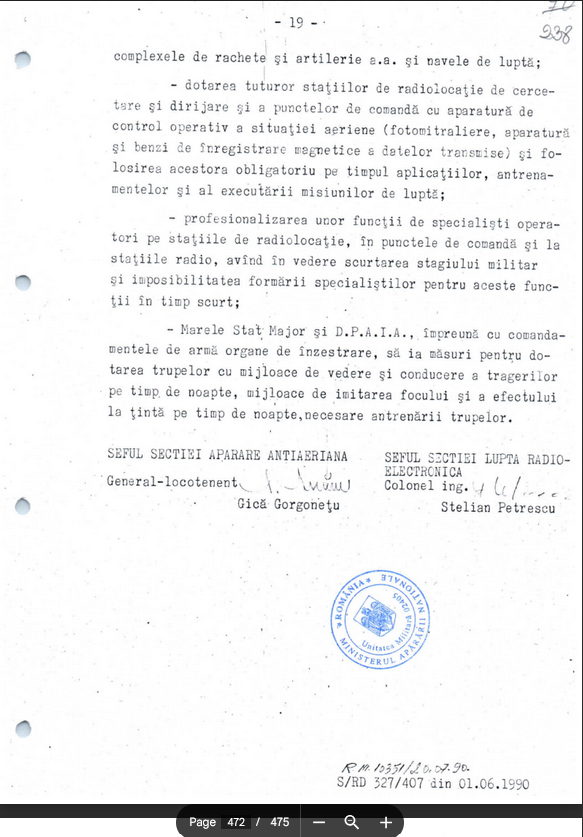

- Pițu’s discussion on page 269 of the Indictment of a 1 June 1990 study collectively by the Defense Ministry’s Chiefs of Staff, CAAT, CAvM (The Military Aviation Command), and the Navy at the very least reveals a glaring contradiction. The document is entitled “Summary of the actions of disinformation and radio electronic jamming executed between 22.12.1989 and 21.01.1990 against (military) units of antiaircraft defense, aviation, and the navy.”[17]

In his quote, Pițu himself refers to the collective military study’s conclusion that “In these [terrorist] actions internal forces, and probably external forces, took part.” Pițu then adds: “The material does not identify the ,internal forces’, but instead just affirms that they were elements loyal to the former [Ceaușescu] regime, which given our investigations and historical reality, is ridiculous” [Rechizitoriul, p. 269, emphasis added]. In other words, he is admitting that the study in question argues that the terrorists existed— thus contradicting his own blanket statements in Romanian media.

- In the above two examples, we see that the prosecutor mischaracterizes a report written three months after the Revolution; and disparages a report from six months after the Revolution, both of which contradict his recent public declarations. Below I have selected an after-action report written 16 months after December 1989 to show that long after the heat of the Revolution had subsided, one of those military structures invoked by Pițu was still unambiguous in maintaining that the terrorists existed.

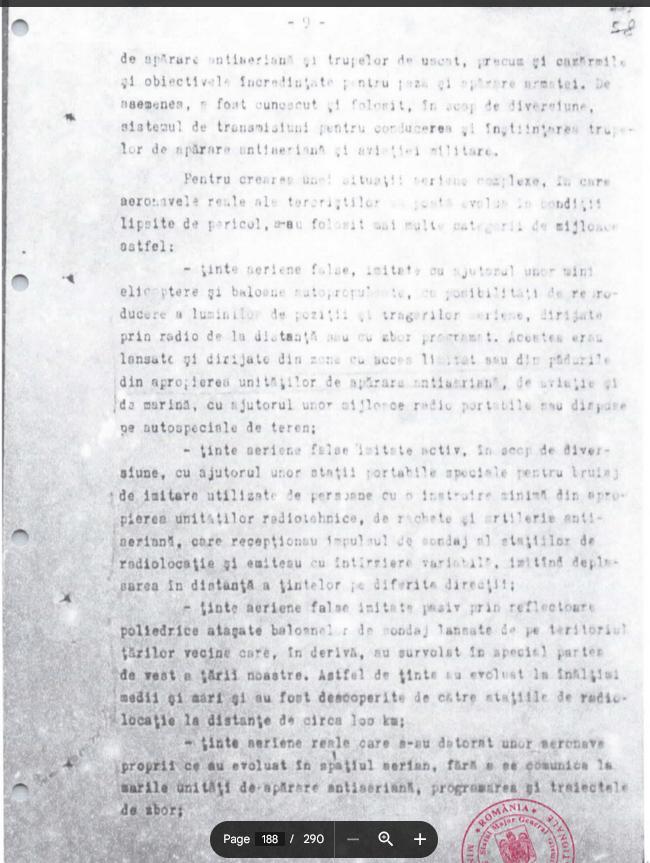

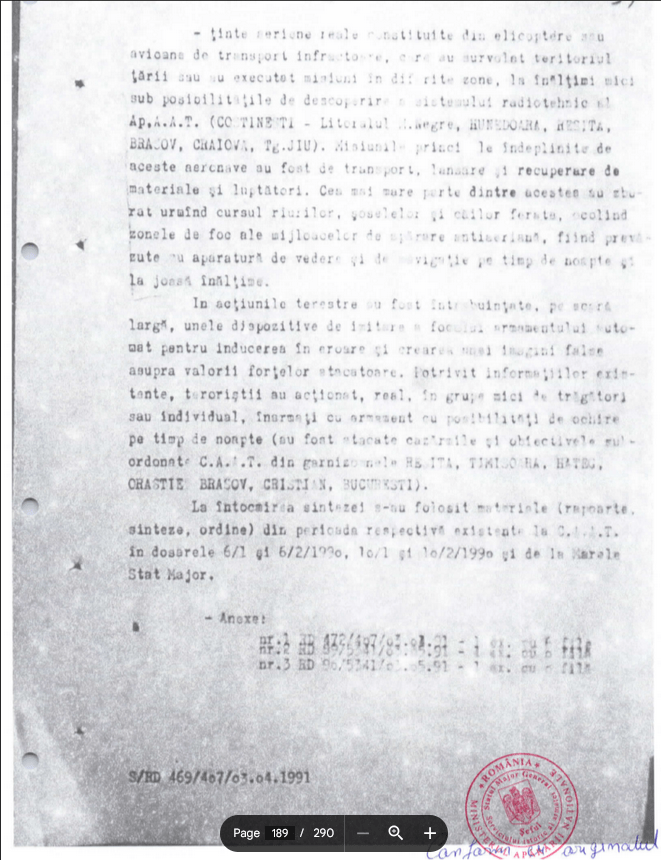

The CAAT document of 3 May 1991 “SUMMARY of military operations undertaken by major units subordinated to the Territorial Antiaircraft Defense Command during the period 22 December 1989 to 17 January 1990” sums up its conclusions as follows:

According to existing information, the terrorists acted, in fact, in small groups of shooters or alone, armed with weapons capable of night-time targeting (barracks and objectives subordinated to the C.A.A.T. from the garrisons at RESITA, TIMISOARA, HATEG, ORASTIE, BRASOV, CRISTIAN, BUCURESTI were attacked).[18]

Thus, the military investigators’ conclusion was that terrorists existed and operated against military units spread across the country. This clearly contradicts Pițu’s repeated public claims about the conclusions of “all” the MApN reports.

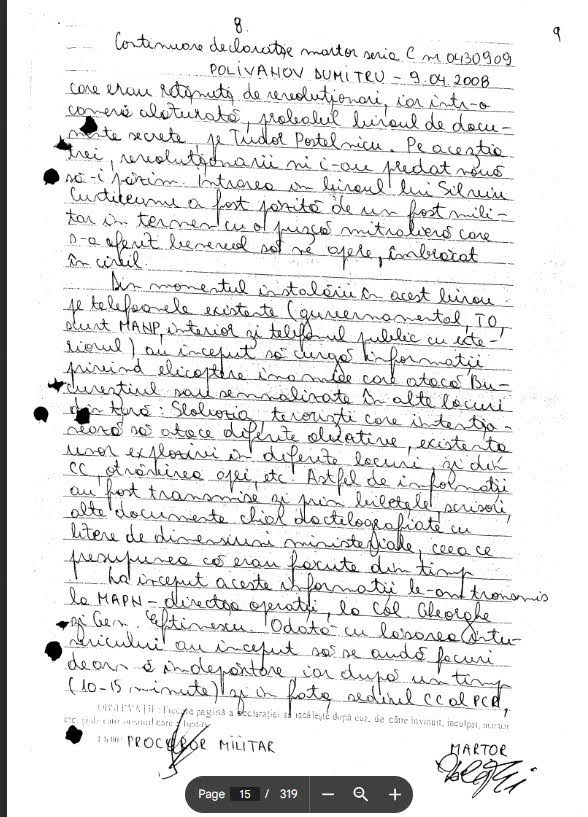

- The next document (MODUL DE PARTICIPARE LA ACȚIUNILE DIN GARNIZOANA BUCUREȘTI AL M.U. (marilor unități) ȘI U. (unităților) SUBORDONATE ARMATEI 1, LA REVOLUȚIA DIN DECEMBRIE) encompasses all units from the First Army and was signed by its commander, General Major Dumitru Polivanov, on 13 September 1990. Once again, this is a document that was drawn up long after the end of the “terrorist” phase of the Revolution. The document is sufficiently detailed and insightful that I will quote extensively from the conclusions it leads with:

- The antirevolutionary forces against which operations were carried out

The principal characteristic of the actions of the antirevolutionary forces consisted of the fact that they did not pursue their goals in a direct manner but rather envisioned the creation of a state of permanent tension, insecurity, and disorder, alternating between harassing the army and psychological (diversionary) warfare.

To attain these goals, antirevolutionary elements began, from the evening of 22 December, to attack civilian objectives in the capital and in other cities (the PCR CC building, Radio, Television, water reservoirs, municipal and county council headquarters, etc.), as well as barracks, munitions depots, and other military objectives.

In the beginning, these operations were chaotic, but as the events unfolded, they became organized, leaving the impression of the operationalization of a well-conceived plan under a centralized leadership.

The heterogenous make-up of the antirevolutionary forces caused confusion among the soldiers who participated in the guarding and defense of different objectives and as a result many of the people who were detained as suspects, were, after summary investigation, released.

In general these forces operated from buildings surrounding objectives, cemeteries, churches, parish residences, sewer entrances, as well as personal cars, pick-ups, and large trucks.

The frequency of the attacks on objectives during the day were [reduced], usually relying on cars, growing in intensity during the night when they would open gunfire from different locations, at irregular intervals, giving the impression of attacks being executed from converging directions.

The operations of the terrorist-antirevolutionary forces reached its greatest intensity during the period 22-26.12, after which the frequency of the attacks against civilian and military objectives gradually fell, ceasing completely beginning with 30.12.

Given how the operations unfolded the conclusion can be drawn that the antirevolutionary forces operated in small groups of 2-5 persons, or sometimes individually, using in many cases gunfire simulators.

The basic plan of these operatives was harassment, applying the principle of “STRIKE AND DISAPPEAR” to create panic, confusion and insecurity among the population and defense forces.

Another tactic that was widely used by the terrorist elements was the interception of telephonic communications and the transmitting of false information, with the goal of causing decisionmakers to make mistakes.

In addition, there was radio jamming on shortwave and high range frequencies [ultrascurte], hindering the leadership of units and subunits.

Their weapons’ arsenal was very diversified, consisting of weapons of different calibers (5,6; 7,62; 7,92; 9; 11 mm), which used normal, explosive, and other bullet types. In addition, they had means of seeing at night, infrared sights, night-vision goggles, and technical tactical means that allowed them to shoot precisely in vital organs, that caused numerous losses among the ranks of the military.

The clothing of the antirevolutionary forces was very diverse, consisting of civilian clothes, military uniforms, or those of the national [Patriotic] guards, sportswear, bulletproof vests, which caused great confusion among the armed forces.

Thus, out of a total of 66 people detained by the units of the First Army during the period of the Revolution, 25 were released to neighborhood associations or relatives, 14 at military units to which they belonged, being either draftees or employees. The other people detailed were turned over to the Militia, the Bucharest Militia Inspectorate, the prosecutors of Sector 5, U.M. 02515 “c” and U.M. 0800.[19]

Further down in this report, Polivanov mentions that “during the period 23-31.12, the First Army suffered the following losses: 20 dead, of which 6 officers, 2 NCOs and 12 draftees and 62 wounded (16 officers, 6 NCOs, and 40 draftees).” These numbers highlight that this was a real conflict, with real casualties. A document such as this, which details the tactics, weapons, equipment, and even ballistics of what the Army clearly saw as an enemy does not in any way substantiate Pițu’s claims that MApN did not believe in the terrorists.

- “Dosar revoluție nou” also includes an after-action report for the southwestern city of Reșița. Notably, this document is dated three years after December 1989 and for units that were far away from the glare of the spotlight of international media coverage—a subtext to Pițu’s argument that the false flag of “invented terrorists” was all “for show.”

During the period 22.12-25.12.1989, the unit [U.M. 01929 Resita] undertook anti-aircraft and terrestrial operations, striking two aerial targets and turning back all attacks directed against the barracks…Beginning with 22.12.1989 at 1145 on the screens of the radio location units there was active noise jamming. Simultaneously with the evolution of the helicopters, we appraise that the enemy used means of visual simulation to cause troops to mistake the real aerial situation.

TERRESTRIAL WARFARE OPERATIONS

The enemy attacked the unit’s command center, the munitions depot, the communications center, and the barracks of UM 01960 and UM 01864 “Ax”.

The attacks were executed mainly at night between 1800 and 0700, in a concentric manner, with gunfire intensifying on certain areas (especially the communications center and the munitions depot), in small groups or individually, with automatic weapons of high cadence, low noise, and probably, night-sights and silencers. The maximum intensity of gunfire was recorded on 24.12.1989 and 25.12.1989 between the hours of 0430 and 0630….

During daylight, reconnaissance outside of the unit of locations from which they fired resulted in the discovery of cartridges and casings from different years but without production lot mention, military clothing, and bloodstains.[20]

The lack of factory markings on the bullets was mentioned by military forces in other parts of the country and shows both a) a design to mislead the military forces and cloak the identity of the shooters and b) longer-term preparation and a plan for the actions that were being carried out against these military units.

In a separate document, Major Iulian Pârvulescu also drew conclusions on the tactics and strategy of those who attacked his unit, from 22 to 26 December 1989. Pârvulesu’s report is noteworthy for its sober portrayal of the threat the terrorists posed, while nevertheless making clear that the terrorists and their attacks were real.

The aerial targets that were discovered by radio technical or visual means did not attack antiaircraft defense equipment or other objectives.

It is probable that the detected targets fulfilled reconnaissance missions in the area over which they flew, collecting information on the operational frequencies of the radio technological equipment, intercepting radio and radio-relay communications, transporting and disembarking groups of “terrorists”, who usually operated on their own.

The attacks were concentric, centering on one or two directions. The attacks usually lasted 15-20 minutes, followed by a pause of 30-40 minutes. To signal the beginning and cessation of operations they used light signals and red or green flares.

Based on the way they operated, we deduced that the enemy did not try to occupy the unit but only tried to prevent the activation of antiaircraft defenses, the physical and psychological exhaustion of the troops, as well as blocking them in their barracks.

They [the terrorists] usually knew the area and how the unit was laid out. They knew the capabilities of our forces and as a result their operations were well-planned and organized.[21]

Fixed intervals of gunfire, identifiable pauses between those intervals, and the use of flares to signal the beginning and ending of an attack are not logically consistent with Pițu’s contention that all gunfire in December 1989 was “friendly fire.”

- Let us look at the January 1990 conclusions of an after-action report by a Bucharest military unit (UM 0251), some of whose personnel found themselves detailed to other parts of the country for training at the time of the outbreak of the Revolution. Some of them ended up defending the Hășdat (UM 01852) unit from 26 to 30 December. Even more so that Reșița, this is obviously an out-of-the-way, out-of-the-media-spotlight location.

Based on the bullet parts found it turns out that the terrorists had automatic weapons of between 5,45 and 5,6 [mm…not in the Army’s arsenal]…Gunfire against the soldiers was executed in the nights of 26/27 and 27/28.12.1989, beginning at 1900 until sunrise.[22]

A different document, entitled “REFERAT privind stării de fapt a acțunilor militare in Municipiul HUNEDOARA in perioadă 22.12.89-28.12.1989” and signed by “Cpt. Coraș Leontin, delegat al Parchetului Militar Timișoara, UM 01933 Hunedoara”, dates from 1991] and states the following:

The attack was concentric and occurred simultaneously against UM 01933 [Hunedoara], UM 01852 [Hăsdat] and the command center…The armed attacks against the barracks occurred on the nights of 22/23; 23/24; 24/25; 26/27 and in a very limited way 27/28 December 1989. The attacks usually began in the evening and ended in the morning; the beginning and end of the attack was preceded by the launching of flares. The goal of the attack was only to create confusion, keep the soldiers confined to their barracks by provoking them, after which they would frequently change the places from which they were firing. [emphasis added][23]

As we have by now seen multiple times, these after-action reports concluded that the terrorist actions were typical early-stage guerrilla warfare tactics of harassment and intimidation. They were not designed to focus on a casualty count, but as terrorists do, to create terror.

- Finally, we look at the 16 February 1990 deposition of Army General Ion Hortopan, Commander of the Infantry and Tank Division. Since prosecutor Pițu invoked among “every MApN structure,” Infantry and Tanks, it follows that the deposition of the commander of those units should have insight into what happened in December 1989 and should speak for those units. Hortopan’s declaration appears four times in Dosarul Revoluției—including in “Dosar revoluție nou”—so it’s even more likely that the prosecutor should have seen its contents. There is much in Hortopan’s deposition of relevance, but for our purposes I will just quote the following:

The terrorist attacks grew in intensity on 23 December and in the evening of that day at a strategy session of the Council of the National Salvation Front, [Iulian] Vlad [the Securitate chief] was asked who was shooting into the Army and the population, to which, he, with the intention of deceiving us—responded that demonstrators, including dubious elements and former prisoners, had entered certain important objectives, formed groups and started to fire at us. During the operations of our troops a number of terrorists who were members of Securitate units were detained, and were given the floor to present the number of the units to which they belonged (U.M. 672F, U.M. 639, U.M. 0106, U.M. 0620), to which Vlad, in order to again deceive us affirmed that perhaps they were fanatics who were operating on their own.[24]

What is important to recognize here is that once confronted with terrorist suspects in the flesh, Vlad’s room for maneuver shrank and he quickly changed to a new tactic—no longer denying their existence by suggesting that they were demonstrators and former prisoners. Instead, he accepted that they were members of the Securitate, while seeking to distance himself from them by suggesting that they acted on their own. It is also worth noting that Vlad’s initial efforts to suggest that the Securitate were not firing and that there were no terrorists would quickly become the primary component of the Securitate’s revisionist history of December 1989. It is also the central component of the 2022 Indictment in the Revolution case, Ruperea blestemului, and prosecutor Pițu’s repeated media statements.

Conclusions:

The evidence presented here shows that prosecutor Pițu’s public statements about the after-action reports drafted by Defense Ministry structures are not true. All the above quoted reports are from among the declassified documents of “Dosar revoluție nou”, which the prosecutor refers to. So it is unlikely that he has missed them, either entirely or just the above sections. There are many more similar military reports and testimonies, which for brevity I have not mentioned in the paper, but were invoked in other works.[25]

Prosecutor Pițu has claimed that the after-action reports drawn up beginning in January 1990 by every Defense Ministry component concluded that the terrorists of December 1989 did not exist. I have shown here, quoting directly from the same documents he invokes, that based on multiple and corroborated sources, these MApN structures, on the contrary, concluded that the terrorists existed. This significant inaccuracy regarding one of the most critical and controversial, and judicially consequential aspects of the Revolution, raises questions about the credibility of his other statements about December 1989.

Why would Pițu ignore or mischaracterize these documents? One answer might be that the prosecutor assumed that nobody would ever have access to or read closely the documents he invokes. (And it would have certainly been more difficult to prosecute the hundreds of Securitate-affiliated snipers than three elderly former officials with waning or non-existent popularity). In part, it must also lie in the uncritical way Romanian journalists interview or write about the statements of a military and judicial authority such as Cătălin Ranco Pițu. It is difficult to gauge how much of this deference is out of respect for, and how much is compliance with, the state and the institution of the military procuracy, as a branch of “justice”. From a political culture perspective, Pițu tells a comforting, seemingly daring, and populist tale that matches the suspicions, prejudices, and partisanship of the interviewers, and which is seductive in the current geopolitical climate and threat posed by Romania’s historic adversary, Russia. Pițu likely knows that such a tale sells in contemporary Romania. One thing is certain, as this article should demonstrate: the deference granted to this former prosecutor goes way beyond what one would expect of somebody interviewing a former official and Pițu’s claims deserve and need to be challenged.

[1] Since 2018, I have written in Romania under the pseudonym, Roland O. Thomasson. This was a strictly personal choice owing to the sensitive nature of my job. I was a CIA intel analyst from 2000 to 2024. I hold a Ph.D. in Political Science from Indiana University (1997). My thanks to Andrei Ursu for his proofreading, helpful edits, and suggested additional materials for citation (see fn. 25).

[2] Cătălin Ranco Pițu: „Ion Iliescu nu ar fi existat fără Ceaușescu,” Față în față cu Ion Cristoiu, 16 mai 2023, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un1Lglkgsdc&t=1550s; Cătălin Ranco Pițu: „În decembrie 1989 au săvârşit crime împotriva umanităţii multe persoane aflate la vârful ierarhiei politico-militare,” interviu luat de Melania Cincea, 21 decembrie 2023, at putereaacincea; INTERVIU EXCLUSIV | Cătălin Ranco Pițu, despre procesul Ceaușeștilor: „Nu eram dependent, în aflarea adevărului, de un document militar sustras” (II), interviu luat de Sergiu Silviu,at independentnews.

[3] For other recent discussions of this question in the wake of the death of Ion Iliescu, see Andrei Ursu, libertatea and Gabriel Andreescu, contributors.

[4] Peter Siani-Davies, The Romanian Revolution of December 1989 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), p. 130; 131.

[5] Aura Alexa Ioan (cu Adrian Popescu-Necșești), “Teroristii Revoluției au certificat de psihopati!” Tinerama, 8-14 October 1996, p. 8.

[6] For the text online, see Popescu Necsesti.

[7] Raluca Grosescu and Raluca Ursachi, “The Romanian Revolution in Court: What Narratives about 1989?” in Vladimir Tismaneanu and Bogdan C. Iacob, Remembrance, History, and Justice. Coming to terms with traumatic pasts in democratic societies. (New York: Central European University Press, 2015), pp. 257-293.

[8] Grosescu and Ursachi, pp. 270-271.

[9] See Grosescu and Ursachi, especially pp. 284-285.

[10] Generalul Magistrat (r) Ioan Dan, Teroriștii din ’89 (Lucman, 2012); General Magistrat (r) Ioan Dan: “Dosarul Revoluției” Adevărul despre Minciuni. Noi probe prezentate de un fost șef al Procuraturilor Militare (Editura BLASSCO, 2015).

[11] See, for example, the January 1990 declaration of Securitate chief General Iulian Vlad (pp. 10-13) and the February 1990 declaration of Army General Ion Hortopan (pp. 316-321) in Teroriștii din ’89.

[12] See Timișoara from 24 decembrie 1993 and 4 ianuarie 1994; Ioan Dan cu Lucian Grigore, România Liberă, 17 iulie 1996.

[13] Cătălin Ranco Pițu: „Ion Iliescu nu ar fi existat fără Ceaușescu,” Față în față cu Ion Cristoiu, 16 mai 2023, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Un1Lglkgsdc&t=1550s.

[14] Cătălin Ranco Pițu: „În decembrie 1989 au săvârşit crime împotriva umanităţii multe persoane aflate la vârful ierarhiei politico-militare,” interviu luat de Melania Cincea, 21 decembrie 2023, at putereaacincea.

[15] INTERVIU EXCLUSIV | Cătălin Ranco Pițu, despre procesul Ceaușeștilor: „Nu eram dependent, în aflarea adevărului, de un document militar sustras” (II), interviu luat de Sergiu Silviu, independentnews.

[16] Dosarul Revoluției, dosar revoluție nou, DOCUMENTE vol. IV, file 70-78.

[17] Dosarul Revoluției, dosar revoluție nou, DOCUMENTE vol. X, file 229-238.

[18] Dosarul Revoluției, dosar revoluție nou, DOCUMENTE vol. I, file 170-180.

[19] Dosarul Revoluției, București, Jurnalul Acțiunilor de luptă vol. 8, file 37-45.

[20] Dosarul Revoluției, dosar revoluție nou, DOCUMENTE vol. IV, file 94-97.

[21] Dosarul Revoluției, dosar revoluție nou, DOCUMENTE vol. IV, file 98-99.

[22] Dosarul Revoluției, Hunedoara vol. 2, file 54-55.

[23] Dosarul Revoluției, Hunedoara vol. 3, file 68-72.

[24] Dosarul Revoluției, Declarații 97 P 1990 vol. V, file 81-88. The same declaration also appears in Deces Gen Milea vol. I; Jilava vol. 175; and CC vol. 105.

[25] For example: Codrescu, Costache, coord. Armata Română în Revoluția din decembrie 1989 (Institutul de Istorie si Teorie Militara, 1994); Bodea, Alexandru. “Variantă la invazia extratereştrilor.” Armata Poporului (21.03.1990, 28.03.1990, 11.04.1990, 09.05.1990, 23.05.1990, 30.05.1990, 6.06.1990); Dan, Ioan, op.cit.; Floca, Mihai, Stoica, Victor. “Unde sunt teroriştii? Pe stradă, printre noi.” Armata Poporului , (13.06.1990, 27.06.1990); Floca, Mihai. “Reportaj la USLA.” Tineretul Liber, 5.01.1990; Paul Abrudan, Sibiul în revoluția din decembrie 1989 (Sibiu: Casa Armatei, 1990); Andrei Ursu, Roland O. Thomasson, in collaboration with Madalin Hodor, Trăgători și Mistificatori. Contrarevolutia Securitătii in Decembrie 1989 (Snipers and Mystifiers. The Securitate Counterrevolution of December 1989), (Polirom, 2019); Andrei Ursu, Roland Thomasson, eds., Căderea unui dictator. Război hibrid și dezinformare în Dosarul Revoluției din decembrie 1989 (The Fall of a Dictator. Hybrid War and Disinformation in the December 1989 Revolution’s File) (Polirom, 2022). For new and ongoing research presenting documents from the Revolution File, see https://rolandothomassonphd.blog/, and https://substack.com/@richhall .