Posts Tagged ‘decembrie 1989’

Armata română în revoluţia din decembrie 1989 (1994/1998): Sibiu

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on April 12, 2010

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged: Armata Romaniei in decembrie 1989, Aurel Dragomir, decembrie 1989, Richard Andrew Hall, Sibiu 1989, USLA geanta diplomat | 1 Comment »

Unde sint teroristii? PE STRADA, PRINTRE NOI (II) (Romania, decembrie 1989)

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on March 30, 2010

Armata Poporului, nr. 26, 27 iunie 1990

Mult incercatul bloc A1

Prinsi intre focuri–ale teroristilor, dintr-o parte, si cele ale militarilor aflati in dispozitivul de aparare al M.Ap.N., din cealalta parte–locatarii blocului A1 (Drumul Taberei, 16) au trait, in zilele Revolutiei din Decembrie, nopti de groaza. Sa-i ascultam.

–Eu, pur si simplu, nu inteleg domnilor, cum unii ziaristi pot fi asa de rai si palavragii. Distrug omul, nu alta! S-au scris in presa fel de fel de minciuni despre ce s-a intimplat aici, in zilele si noptile ce au urmat fugii lui Ceausescu. Unii s-au apucat sa arate–culmea nerusinarii!–ca nici n-au fost teroristi. Pe noi, insa, nu ne-a intrebat nimeni: ce am trait, ce am simtit atunci, cum am supravietuit…

Si spre a fi mai convingatoare, doamna Stela Baila (scara B, apart. 26) ne arata o cutie cu…gloante (18 la numar), pe care le-a strins din camere.

–Cum a inceput lupta?

–Era pe 22 decembrie. In jurul orei 21,00 am vazut, aproape de poarta Centrului de Calcul, un TIR mare, un fel de sa lunga. Soldatii nici nu apucasera sa ia pozitie de lupta. De sub masina s-a deschis focul: atit spre Ministerul Apararii Nationale, cit si spre noi. Tirul era foarte intens, cred ca de sub masina trageau peste 20 de indivizi. Un glont mi-a trecut pe deasupra capului si s-a infipt, uitati-i urma, sub tavan. Ce a urmat, nu va mai spun. Ne-am refugiat in camera din spate, dar nici acolo n-am avut parte de liniste: din parculet, se auzeau multe strigate, apoi a inceput rapaiala. De pe toate blocurile se tragea! Tocmai umblam la televizor, il reglam, cind un glont a lovit in perete, deasupra televizorului, la citeva zeci de centimetri de capul meu. M-am ales doar cu o rana la mina stinga. Dupa ce teroristii ne-au mai “onorat” cu un glont, am fugit in baie. Dimineata, geamurile erau faramitate.

Din aceeasi directie, dinspre blocul B4, s-a tras si in apartamentul vecin. Gaura din geam se afla la aceeasi inaltime cu cea de pe perete: 1,45 m. Dat fiind ca apartamentul se gaseste la etajul 1, este evident ca teroristul a deschis foc dintr-un loc situat la aceeasi inaltime. De la locatarii acestui apartament (27), aflam ca teroristii erau imbracati intr-un fel de salopete, probabil de culoare gri.

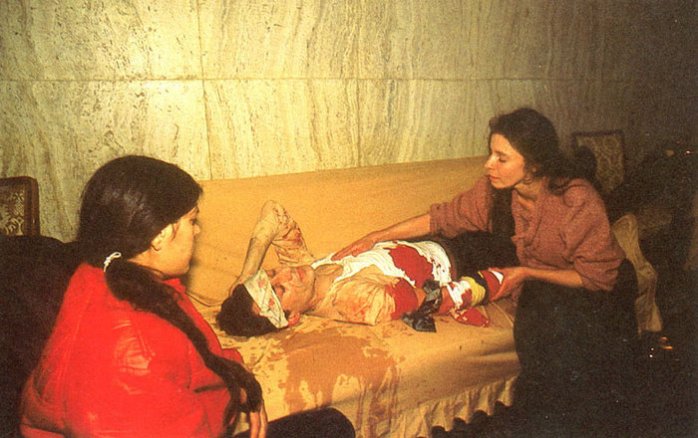

–Da, i-am vazut cu ochii nostri. Alergau ca niste speriati prin parculet, de la un bloc la altul, isi aminteste doamna Maria Cotofana. Dupa miezul noptii, in careul format din cele trei blocuri a avut locu un violent schimb de focuri. Apoi, am auzit batai puternice in usa. “Deschideti, sintem armata, avem raniti!”–auzeam de pe scari. Am primit si noi un ranit–il cheama Cristian Popescu si niste student la Academia Tehnica Militara–impreuna cu un coleg. Imedia cei doi tineri s-au repezit la balcon, sa traga in teroristii care le-au ucis colegii. Foarte greu i-am determinat sa renunte, le-am explicat ca teroristii ne “avertizasera” deja si ne vor face zob apartamentul. Ii vedeam cum se chinuiesc privind neputinciosi cum banditii scuipau moarte si foc de pe blocul B3…

…

“Au tras din blocul meu!!!”

Exista locatari care i-au vazut foarte de aproape pe teroristi, au discutat cu ei. Unul din acesti oameni a acceptat sa ne povesteasca patania sa, dar cu conditia sa nu-i precizam identitatea. Intimplarea a avut loc in aceeasi noapte: 22/23 decembrie 1989.

–Sa tot fi fost 12,30-1,00, cind am auzit “poc, poc, poc”–cineva umbla pe balcon. Fiindca am instalatie electrica acolo, am aprins lumina. Am deschis prima usa ce dadea spre balcon si am vazut un tinar de 24-25 de ani: brunetel, creol, cu parul andulat, slabut. Purta of gluga bej, iar pe deasupra un fel de veston kaki. Inapoi lui, pe lada mai era unul. Grozav m-am speriat: “Deschideti, deschideti”–mi-a strigat brunetul. Am raspuns instantaneu: “Nu se poate, e militia la mine, e militia la mine!” si am inchis usa la loc. El a scos ceva din buzunar–un corp rotund–si a spart geamul usii din exterior. Am fugit, iar in urma mea au rasunat focuri de arma.

Intr-adevar, pe peretele opus balconului sint citeva gauri: acestea nu puteau fi provocate decit de gloante trase din balcon. Din acest balcon–asa cum ne-a relatat locotenentul Marius Mitrofan–s-a tras si asupra studentilor de la Academia Tehnica Militara.

–L-ati recunoaste pe cel care a tras?

–L-am si recunoscut! Dar ma opresc aici, ca si asa am spus prea multe!

Sa mai adaugum ca, pe 23 decembrie, cind gazda noastra a povestit scena cu balconul, un vecin, “binevoitor,” i-a spus: “ti s-a nazarit.”

Foc concentrat asupra Centrului de calcul!

Spre Centrul de Calcul al M.Ap.N. teroristii si-au indreptat cu predilectie armele. Oricine poate constata asta. Daca s-ar fi inarmat cu putina rabdare, gazetarii revistei “Le Point” ar fi putut numara, in peretele frontul al cladirii, circa 300 urme de gloante. La care trebuie adaugate si gaurile care se mai vad, inca, in geamuri. Sigur, geamurile ciuruite au fost schimbate, dar,–prevazatori si rigurosi–, cei din Centrul de Calcul, au avut grija sa le fotografieze. Avem, la redactie, cliseele respective si le putem pune la dispozitia oricui. Ne este imposibil sa credem ipoteza cu “confuzia generala” a confratilor francezi. Pentru ca aici nu este vorba de doua, trei focuri–scapate, la un moment dat, intr-o directie gresita–, ci de sute de gloante trimise cu buna stiinta, nopti de-a rindul, asupra unui obiectiv militar. Si vizind cu prioritate birourile cadrelor cu functii de raspundere.

S-a tras nu numai din strada, ci, in special, de la etajele superioare ale cladirilor de peste drum.

–Noi nu avem caderea sa acuzam pe nimeni–arata colonelul Marcel Dumitru. Dar nu ne putem mira indeajuns de faptul ca nimeni din cei in drept nu a initiat pina acum o cercetare. Nu stim cine a tras, dar stim, cu destula precizie, de unde s-a tras in noi. Cind copacii erau desfunziti, privind prin gaurile produse de gloante in geamurile noastre–avem geamuri duble–vizam tocmai acoperisul, balconul, fereasta de unde s-a tras?

De altfel, cu pricepere de artilerist, pe baza observatiilor facute in acele vile de decembrie, maiorul Vasile Savu a intocmit o schema cu locurile de unde s-a tras asupra Centrului de Calcul. Numaram pe schema peste 25 puncte de foc, citeva din acestea coincid cu cele indicate de studentii Academiei Tehnice Militare. In “Le Point” se arata: “Desigur, citiva securisti, infierbintati, au tras pe strada, de pe acoperisuri. Dar nu era decit o mina de oameni, cei multi fiind falsii “teroristi”…armata a amplificat roulu securistilor si a plasat ea insasi falsi teroristi in diferite cartiere ale capitalei.” Ce om cu mintea intreaga poate accepta ideea ca armata a ordonat unor membri ai ei sa traga asupra proprilului minister?!!

Centrul de Calcul este doar una din cladirile aflate in localul M.Ap.N. Nu vom sti niciodata, cu exactitate cite gloante s-au tras asupra integrului complex. Oricum, in comparatie cu cele ce au tintit Centrul de Calcul, acestea sint mult mai multe, ele producind victime mai ales in rindurile personalului neadapostit.

Sa mai amintim ca in 22/23 decembrie, tot inainte de a intra in sediul M.Ap.N.–deci in aceleasi conditii, ca si cei cinci studenti–au cazut un ofiter, un subofiter, si doi soldati dint-o unitate de parasutisti. Tot aici Regimentul de Garda a avut 9 mortii–doi ofiteri si sapte soldati–toti impuscate dupa ce intrasera in dispozitivul de aparare constituit in curtea ministerului. Deci au cazut, in total, 18 eroi. Vom afla, vreodata, cine-i are pe constiinta?

(Maior Mihai Floca si Capitan Victor Stoica, “Unde sint teroristii? PE STRADA, PRINTRE NOI (II), Armata Poporului, 27 iunie 1990, p. 3)

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged: 27 iunie 1990, Armata Poporului, decembrie 1989, mihai floca, nr. 26, PRINTRE NOI (II), Unde sint teroristii? PE STRADA, victor stoica | Leave a Comment »

decembrie 1989: in privinta ‘turistilor rusi,” cum au reactionat Securitatea si Ambasadorul Roman la Moscova? (documentele din Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe (AMAE), Telegrame, publicate de CWIHP)

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on March 14, 2010

Este nemaipomenit ca documentele diplomatice disponsible de pe site-ul Wilson Center (Cold War International History Project, www.wilsoncenter.org/topics/pubs/e-dossier5.pdf, vezi mai jos) n-au fost invocate, retraduse, sau folosite in nici un fel in Romania pana acum. Daca cu adevarat regimul ceausist si mai ales securitatea credeau ca acesti “turisti rusi” sau “turisti sovietici” au fost agenti acoperiti si faceau o lovitura de stat, incepand cu evenimentele din Timisoara, de ce tocmai ei (“turisti rusi” in tranzit) au fost lasati sa calatoreasca prin tara dupa 17 decembrie 1989, si de ce “pericolul” acesta n-a fost ridicat in discutii diplomatice cu sovietici in aceste zile?

Este semnificativ ca Generalul Iulian Vlad, seful Securitatii, n-a suflat nici o vorba in timpul sedintei Comitetului Politic Executiv al CC al P.C.R. din ziua de 17 decembrie 1989 despre presupusi rolul “turistilor rusi” in ceea ce se intimpla la Timisoara. DE FAPT IN NICI O TELECONFERINTA SAU SEDINTA CPExului din saptamana 17-22, NIMENI (CU EXCEPTIA LUI NICOLAE CEAUSESCU) N-AU VORBIT DESPRE ASA-ZISUL ROL AL “TURISTILOR RUSI/SOVIETIC” (De exemplu, vezi faptul ca nici Radu Balan sau Ion Coman n-a mentionat acest lucru in teleconferinta de 17 de la Timisoara http://mariusmioc.wordpress.com/2009/03/25/teleconferinta-lui-ceausescu-din-17-dec-1989/) De ce? Ideea venea din mintea lui Nicolae Ceausescu si faptul ca securistii si altii folosesc acest “argument” dupa decembrie 1989 vine numai dintr-o perspectiva RETROSPECTIVA:

In his 1992 book, he [the chief of the Securitate’s Counter-espionage Directorate, Colonel Filip Teodorescu] developed further on this theme, specifically focusing on the role of “Soviet tourists:”

“There were few foreigners in the hotels, the majority of them having fled the town after lunch [on 17 December] when the clashes began to break out. The interested parties remained. Our attention is drawn to the unjustifiably large number of Soviet tourists, be they by bus or car. Not all of them stayed in hotels. They either had left their buses or stayed in their cars overnight. Border records indicate their points of entry as being through northern Transylvania. They all claimed they were in transit to Yugoslavia. The explanation was plausible, the Soviets being well-known for their shopping trips. Unfortunately, we did not have enough forces and the conditions did not allow us to monitor the activities of at least some of these ‘tourists’” (Teodorescu, 1992, p. 92).

As I have written before, if it was obvious before 18 December, as these Ceausescu regime officials claim, that “Soviet tourists” were involved in the events in Timisoara, then why was it precisely “Soviet travelers coming home from shopping trips to Yugoslavia” who were the only group declared exempt from the ban on “tourism” announced on that day (see AFP, 19 December 1989 as cited in Hall 2002b)? In fact, an Agent France-Presse correspondent reported that two Romanian border guards on the Yugoslav frontier curtly told him: “Go back home, only Russians can get through”!!! The few official documents from the December events that have made their way into the public domain show the Romanian Ambassador to Moscow, Ion Bucur, appealing to the Soviets to honor the Romanian news blackout on events in Timisoara, but never once mentioning—let alone objecting to—the presence or behavior of “Soviet tourists” in Romania during these chaotic days of crisis for the Ceausescu regime (CWHIP, “New Evidence on the 1989 Crisis in Romania,” 2001). It truly strains the imagination to believe that the Romanian authorities were so “frightened” of committing a diplomatic incident with the Soviets that they would allow Soviet agents to roam the country virtually unhindered, allowing them to go anywhere and do anything they wanted.

traducere de catre Marius Mioc http://mariusmioc.wordpress.com/2009/10/16/rich-hall-brandstatter-12/

După cum am mai scris înainte, dacă ar fi fost vădit înainte de 18 decembrie, după cum afirmă aceşti oficiali ai regimului Ceauşescu, că “turiştii sovietici” erau amestecaţi în evenimentele din Timişoara, de ce au fost tocmai “călătorii sovietici întorcîndu-se din excursiile pentru cumpărături din Iugoslavia” singurul grup care a fost exceptat de la interzicerea turismului anunţată în acea zi (vezi Agenţia France Presse, 19 decembrie 1989, după cum a fost citată în Hall, R. A., 2002, “The Securitate Roots of a Modern Romanian Fairy Tale: The Press, the Former Securitate, and the Historiography of December 1989” [Rădăcinile securiste ale unui basm românesc modern: Presa, fosta securitate şi istoriografia lui decembrie 1989], “Part 2: Tourists are Terrorists and Terrorists are Tourists with Guns” [Partea a 2-a: Turiştii sînt terorişti şi teroriştii sînt turişti înarmaţi], Radio Free Europe “East European Perspectives” [Radio Europa Liberă “Perspective est-europene], Vol. 4, nr. 8). În fapt, un corespondent al agenţiei France Press a relatat că doi grăniceri români de la graniţa cu Iugoslavia i-au spus tăios: “Întoarce-te acasă, numai ruşii au voie să treacă”!!! Puţinele documente oficiale despre evenimentele din decembrie 1989 care au devenit disponibile public îl arată pe ambasadorul român la Moscova, Ion Bucur, cerîndu-le sovieticilor să nu relateze despre evenimentele din Timişoara (după cum făcea şi presa română), dar fără să menţioneze niciodată, cu atît mai puţin să protesteze, faţă de prezenţa sau comportamentul “turiştilor sovietici” în România în timpul acelor zile haotice de criză pentru regimul Ceauşescu (CWHIP, “New Evidence on the 1989 Crisis in Romania,” 2001). Este o forţare a imaginaţiei să se creadă că autorităţile române erau aşa de “înfricoşate” de a provoca un incident diplomatic cu Uniunea Sovietică încît ar fi îngăduit agenţilor sovietici să cutreiere ţara nestingheriţi, lăsîndu-i să meargă oriunde şi să facă orice doresc.

——————————————————————————-

Document 1

Telegram from the Romanian Embassy in Moscow

to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Bucharest)

18 December 1989, 12:35 pm

Comrade Ion Stoian, Candidate Member of the Executive Political Committee

5

of the Central

Committee of the Romanian Communist Party (CC PCR), Foreign Minister,

1. We took note of your instructions (in your telegram nr. 20/016 750 of 17 December

1989)

6

and we will conform to the orders given.

We have taken actions to implement your instructions, both at the consular section of the

Embassy and at the General Consulate in Kiev.

[Furthermore] we would [like to] inform that the Director of the TAROM

7

office [in

Moscow] received, through his own channels, instructions regarding foreign citizens traveling to

our country.

2. Considering the importance of the problem and the nature of the activity of issuing

visas to Soviet citizens, we would like to mention the following problems [which have arisen],

[problems] to which we would like you to send us your instructions as soon as possible.

A. Beginning with the morning of 18 December of this year, Soviet citizens have begun

to make telephonic inquiries to the Embassy from border crossings into Romania, implying that

there are hundreds of vehicles which are not allowed to cross [the border] into our country. [W]e

anticipate that the Soviet government will ask for an explanation with regard to this decision

taken [by the Romanian government]. We ask that instructions be sent explaining the way we

must deal with the situation if it arises.

B. Continuously, at the Consular Section, we have given transit visas to Soviet Jews

who have the approval [of the Soviet government] to emigrate to Israel, as well as to foreign

students studying in the Soviet Union. Since the director of the TAROM office has received

instructions that he is to continue boarding transit passengers without any changes, we would like

to request instructions with regard to the actions we must take in such situations.

C. Considering the great number of Romanian citizens that are living in the Soviet

Union who during the holidays travel to our country, we would like to know if we should issue

them visas.

D. For business travel to Romania, the instructions given to TAROM are that the

applicants must show proof [of an invitation] from the ir Romanian partners.

Please inform whether we must inform the Soviet government of this requirement since

the official Soviet delegations use, for their travels to Bucharest, exclusively AEROFLOT

8

and

that we have no means of [us] controlling the planning of such travels.

5

Politburo

6

The 17 December telegram is not available at this time.

7

The state-owned Romanian National Airline— Transportul Aerian Român

8

Soviet Airlines.

| Page 5 |

We are experiencing similar problems in dealing with the possible situation of Soviet

citizens with tourist passports, which have received a visa prior to the [17 December 1989]

instructions and who will be using AEROFLOT for their travel to Romania.

E. We request that the Civil Aviation Department send instruction to the TAROM office

regarding the concrete actions that should be taken in connection with the 20 December flight

[from Moscow to Bucharest] so that they are able to make the final decision, during boarding,

regarding the passengers [that are to be allowed on to the plane].

We would [like to] mention that the list of passengers is given to the Director of

TAROM, from AEROFLOT or other [travel] companies, without any mention of the purpose of

the trip.

(ss) [Ambassador] Ion Bucur

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe

(AMAE), Moscow/1989, vol. 10, pp. 271-272. Translated for CWIHP by Mircea Munteanu]

Document 2

Telegram from the Minister of Foreign Affairs (Bucharest) to all Embassies

19 December 1989

Cde. Chief of Mission,

In case you are asked during the exercise of your diplomatic attributes (we repeat: only in

case you are asked) about the so-called events taking place in Timisoara, reiterate, with all clarity,

that you have no knowledge of such events. After this short answer, and without allowing you to

be drawn into a prolonged discussion, resolutely present the following:

We strongly reject any attempts to intervene in the internal affairs of S.R. Romania, a free

and independent state. [We reject] any attempt to ignore the fundamental attributes of our

national independence and sovereignty, any attempt at [harming] the security interests of our

country, of violating its laws. The Romanian [government] will take strong actions against any

such attempts, against any actions meant to provoke or cause confusion, [actions] initiated by

reactionary circles, anti-Romanian circles, foreign special services and espionage organizations.

The [Romanian] socialist state, our society, will not tolerate under any circumstances a violation

of its vital interests, of the Constitution, and will take [any] necessary action to maintain the strict

following of the letter of the law, the rule of law, without which the normal operation of all

spheres of society would be impossible. No one, no matter who he is, is allowed to break the laws

of the country without suffering the consequences of his actions.

Instruct all members of the mission to act in conformity with the above instructions.

Inform [the Minister of Foreign Affairs] immediately of any discussions on this topic.

Aurel Duma [Secretary of State

9

, MFA]

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe

(AMAE), Ministry Telegrams, vol. 4/1989, pp. 387-388. Translated for CWIHP by Mircea

Munteanu.]

9

Assistant Deputy Minister— Secretar de State.

| Page 6 |

Document 3

Telegram from the Romanian Embassy in Moscow

to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

21 December 1989, 7:35 am

Cde. Ion Stoica, Minister [of Foreign Affairs],

Cde. Constantin Oancea, Deputy Minister [of Foreign Affairs],

DRI

10

On 20 December 1989, during a discussion with G. N. Gorinovici, Director of the

General Section for Socialist Countries in Europe, I expressed [the Romanian government’s] deep

indignation in regards with the inaccurate and tendentious way in which the Soviet mass media is

presenting the allegedevents taking place in Timisoara. I stressed that the stories made public by

radio and television are based on private, unofficial sources, and not on truthful information.

Many stories refer to the Hungarian press agency MTI, which is known for its antagonistic

attitude towards our country. I mentioned that V. M. Kulistikov, Deputy Chief Editor of the

publication Novoe Vremia, during an interview given to Radio Svoboda, expressed some opinions

vis-ŕ-vis Romania with are unacceptable. I brought to his [Gorinovici’s] attention the fact that on

19 December, Soviet television found it necessary to air news regarding the events in Timisoara

in particular, and in Romania in general, four separate occasions.

I argued that such stories do not contribute to the development of friendly relations

between our two countries and that they cannot be interpreted in any other way but as an

intervention in the internal affairs concerning [only] the Romanian government. I asked that the

Soviet government take action to insure the cessation of this denigration campaign against our

country and also to prevent possible public protests in front of our embassy. Gorinovici said that

he will inform the leadership of the Soviet MFA. In regards with the problems raised during our

discussion, he said that, in his opinion, no campaign of denigrating Romania is taking place in the

Soviet Union. “The mass media had to inform the public of the situation,” Gorinovici indicated,

in order to “counter-balance the wealth of information reaching the Soviet Union through

Western airwaves. Keeping silent on the subject would have only [served to] irritate the Soviet

public.” Following this statement, he recapitulated the well-known Soviet position with regards to

the necessity of allowing a diversity of opinions and ideas be expressed in the context of

informing the Soviet public about world events.

(ss) [Ambassador] Ion Bucur

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe,

Moscow/1989, vol. 10, pp. 297-298. Translated for CWIHP by Mircea Munteanu.]

10

Directia Relatii I— Directorate 1, Socialist Countries, Europe

| Page 7 |

Document 4

Informational Note from the Romanian Embassy in Moscow

to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Bucharest)

21 December 1989, 8:00 am

Cde. Ion Stoian, Minister of Foreign Affairs,

Cde. Costantin Oancea, Deputy Foreign Minister,

DR1

During the evening of 20 December 1989, I was invited in audience at I. P. Aboimov,

Deputy Foreign Minister of USSR. He related to me the following:

1. Lately, the Soviet press published news in connection to events unfolding in Romania,

specifically with the events in Timisoara. It is true that some of the published materials are based,

generally, on foreign [i.e. not Romanian] sources. It is evident that the [Soviet] mass media need

information on the basis of which to inform the public. Aside from this, during meetings with

foreign journalists, there were many requests addressed to the Soviet [government] to state its

position in regards with the events taking place in Romania as they were presented by various

press agencies. Furthermore, during his recent visits in Brussels and London, [Foreign Minister

Edward] Shevardnadze

11

was asked to state his opinion vis-ŕ-vis those events. In London, after

the official talks ended,

12

the Soviet Foreign Minister had a difficult time convincing [Prime

Minister Margaret] Thatcher that there should be no comments to the press on the events

allegedly taking place in Romania. The [Romanian] Foreign Ministry is also informed that

interest in this matter was expressed during working meetings of the Second Congress of the

People’s Deputies taking place in Moscow at this time.

13

The [Soviet] ambassador in Bucharest

was instructed to contact the Romanian government and obtain, from authorized officials,

information to confirm or refute the version of the events distributed by foreign press agencies.

To this date, the Soviet Embassy was unable to obtain and transmit any such information.

Due to such problems, the Soviet government asks that the Romanian government send

an informational note, even one that is restricted [cu caracter închis] regarding the events that are

really taking place in Romania. [The Soviet government] is interested in receiving information

that is as comprehensive as possible. If information is not received, it would be extremely

difficult to create an effective set of directions for the Soviet mass media, with which there are,

even so, many difficulties. [The Soviet government] is worried that, based on the news reported

in the press, some of the deputies participating at the sessions, would ask that the 2

nd

Congress of

the People’s Deputies take a position vis-ŕ-vis the alleged events taking place in Romania. The

MFA prepared for the deputies an information note in which it stresses that it does not have any

official information, but it is possible that this argument will not accepted long. Based on the

information available to the MFA, the Congress will adopt a resolution with regards to the US

military actions in Panama.

Of course, there is no connection between the two events. In Panama, a foreign military

intervention is taking place, while in Romania the events are domestic in nature. I. P. Aboimov

stressed his previous request that the Romanian government send, in the spirit of cooperation

11

Edward Sevardnadze traveled to Brussels and London at the end of 1989. On 19 December he met at

NATO HQ with NATO Secretary General Manfred Woerner and Permanent Representatives of NATO

countries.

12

Prime Minister Thatcher met Shevardnadze in London on 19 December 1989.

13

The Second Congress of the People’s Deputies began its session on 12 December 1989.

| Page 8 |

between the two countries, an informational note truthfully describing the current situation in the

country.

2. The Soviet MFA received a series of complaints that the border between the Soviet

Union and Romania has been closed for Soviet citizens, especially tourists. The Soviet

government was not previously informed with regards to this development. [T]his omission

causes consternation. The Soviet government is not overly concerned with the situation, but

[notes that] it creates difficulties with tourists that have already paid for and planned their

vacations accordingly.

3. With regards to the above statements, I said that I would, of course, inform Bucharest

of this. At the same time, I expressed the displeasure [of the Romanian government] with the fact

that the Soviet radio, television and newspapers have distributed news regarding events in

Romania taken from foreign news agencies, agencies that are distributing distorted and overtly

antagonistic stories regarding the situation in Romania. I gave concrete examples of such stories

published in newspapers such as Izvestia, Pravda, Komsomolskaia Pravda, Krasnaia Zvezda,

stories distributed by western press agencies as well as the Hungarian Press Agency MTI, which

is known for its antagonistic attitude towards our country. In that context, I mentioned that the

Romanian government has not requested that the Soviet Union inform it concerning events

unfolding in Grozny or Nagornîi-Karabah, nor has it published any news stories obtained from

Western press agencies, believing that those [events] are strictly an internal matter concerning

[only] the Soviet government.

I expressed my displeasure with the fact that some Soviet correspondents in Bucharest—

including the TASS correspondent— have transmitted materials from unofficial sources, which

contain untruthful descriptions of the events and which create in [the mind of] the Soviet public

an erroneous impression of the situation existing in our country. I stressed the point that such

behavior is not conducive to strengthening the relationship between our peoples and

governments, on the contrary, causing [only] serious damage [to said relationship]. I brought to

the attention of the Deputy Foreign Minister in no uncertain terms that a resolution of the

Congress of the People’s Deputies [concerning] the alleged events taking place in Romania

would be an action without precedent in the history of relations between the two countries and

would cause serious damage to the relationship.

At I. P. Aboimov’s question, I described the events regarding the situation of pastor

László Tökes, as described in your memorandum, stressing that this information does not have an

official character. I presented, in no uncertain terms, the decision of [the government of] Romania

to reject any attempts at interference in the internal matters of Romania. I expressed the decision

[of the Romanian leadership] to take any necessary measures against disruptive and diversionary

actions perpetrated by reactionary, anti-Romanian circles, by foreign special services and

espionage agencies (servicii speciale si oficinele de spionaj staine). With regard to the issue of

tourists crossing the border in Romania, I said that I did not posses an official communication in

this regard. I suggested that some temporary measures were adopted due to the need to limit

access of certain groups of tourists [in the country]. [Those limitats were imposed] due to

difficulties in assuring their access to hotel rooms and other related essential conditions. Those

limitations do not apply to business travel or tourists transiting Romania. I reminded [I. P.

Aboimov] that the Soviet government had introduced at different times such limitations on travel

for Romanian tourists to certain regions [of the Soviet Union] (Grozny and Armenia), which

[had] provoked dissatisfaction.

4. The conversation took place in a calm, constructive atmosphere.

(ss) [Ambassador] Ion Bucur

| Page 9 |

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe

(AMAE), Telegrams, Folder: Moscow/1989, vol. 10, pp. 299-302. Translated for CWIHP by

Mircea Munteanu.]

Document 5

Information Note from the Romanian Embassy in Moscow

to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

21 December 1989, 2:00 pm

Comrade Ion Stoica, Minister of Foreign Affairs,

1. On 21 December 1989, at 12:00 pm, I paid a visit to Deputy Foreign Minister I. P.

Aboimov to whom I presented a copy of the speech given by Comrade Nicolae Ceausescu,

General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party [PCR] and President of the Socialist

Republic of Romania [SRR], on the 20 December 1989 over radio and television. I. P. Aboimov

made no comments with regard to the speech. He requested that the Soviet side receive

information as to whether,during the events taking place in Timisoara, any deaths had occurred

and what the current situation in the city was.

2. Aboimov said that during the 19 December discussions between the Soviet ambassador

in Bucharest and Cde. Nicolae Ceausescu, the latter expressed his disapproval with the official

declarations made by Soviet officials concerning the events in Timisoara. He [Ceausescu] said

that those [actions taking place in Timisoara] are the result of strategies developed beforehand by

[member nations of] the Warsaw Treaty Organization (WTO). [Ceausescu] suggested that certain

officials in Bucharest told ambassadors from socialist countries that they have information with

respect to the intention of the Soviet Union to intervene militarily in Romania.

As for the so-called official declarations [Aboimov added], they probably refer to a reply

made by Cde. E[dward] Shevardnadze, [Soviet] Minister of Foreign Affairs to a question from a

Western journalist during his trip to Brussels. [The question] referred to the events in Timisoara

and [the question of] whether force was used there. Cde. Shevardnadze answered that “I do not

have any knowledge [of this], but if there are casualties, I am distressed.” Aboimov said that, if

indeed there are casualties, he considered [Shevardnadze’s] answer justified. He stressed that E.

Shevardnadze made no other specific announcement in Brussels [with regards to the events in

Timisoara]. Concerning the accusations that the actions [in Timisoara] were planned by the

Warsaw Pact, and specifically the declarations with regard to the intentions of the USSR,

14

Aboimov said that, personally, and in a preliminary fashion, he qualifies the declarations as

“without any base, not resembling reality and apt to give rise to suspicion. It is impossible that

anybody will believe such accusations. Such accusations”— Aboimov went on to say— “have

such grave repercussions that they necessitate close investigation.”

He stressed that the basis of interaction between the USSR and other governments rested

on the principles of complete equality among states, mutual respect, and non-intervention in

internal affairs.

(ss) [Ambassador] Ion Bucur

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe

(AMAE), Moscow/1989, vol. 10, pp. 303-304. Translated for CWIHP by Mircea Munteanu.]

14

Ceausescu repeatedly accused the Soviet Union in December 1989 of planning an invasion of Romania.

| Page 10 |

Document 6

Telegram from the Romanian Embassy in Moscow

to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Bucharest)

22 December 1989, 07:30 am

Cde. Constantin Oancea, Deputy [Foreign Affairs] Minister

Directorate 1— Socialist Countries, Europe

During a conversation between N. Stânea and V. L. Musatov, Deputy Director of the

International Department of the Central Committee (CC) of Communist Party of the Soviet Union

(CPSU) [Musatov], referring to the situation in Eastern European countries, declared:

The processes taking place [in Eastern Europe] are the result of objective needs.

Unfortunately, these processes taking place are [sometimes] incongruous. In some countries, such

as Hungary and Poland, the changes that took place went outside the initial limits planned by the

[local] communists, who have [now] lost control. The situation is also becoming dangerous in

Czechoslovakia and the German Democratic Republic [GDR]. At this time, in Bulgaria the

[Communist] Party is trying to maintain control, however, it is unknown which way the situation

will evolve. As far as it is concerned, the CPSU is trying to give aid to the communists.

Representatives of the CC of the CPSU have been or are at this time in the GDR [and]

Czechoslovakia to observe the situation personally. The attitude towards the old leadership is

regrettable. For example, [East German Communist Party leader] E[rich] Honecker will be

arrested. In the majority of these countries there are excesses against the communists. The Soviet

government is preoccupied with the future of “Our Alliance.” [The Soviet government] is

especially interested in the evolution of events in the GDR, in the background of the discussions

taking place regarding reunification. The Soviet Union is following all these events, but is not

getting involved in the internal affairs of the respective countries.

.

(ss) [Ambassador] Ion Bucur

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe

(AMAE), Moscow/1989, vol. 10, p. 313. Translated for CWIHP by Mircea Munteanu.]

Document 7

Telegram from the Romanian Embassy in Moscow

to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Bucharest)

22 December 1989, 04:20 pm

Cde. Ion Stoian, Minister of Foreign Affairs,

| Page 11 |

On 22 December 1989, at 02:00 pm I. P. Aboimov, Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister,

called me at the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Accompanying me was I. Rîpan, [Embassy]

secretary. V. A. Lapsin, [Soviet MFA] secretary was also present.

Aboimov said that he was instructed to present, on behalf of the Soviet leadership, the

following reply to the message sent [by the Romanian government] through the Soviet

ambassador in Bucharest [during his discussion with Nicolae Ceausescu on 19 December].

“The message sent [by] the Romanian nation on 20 December of this year, has been

carefully examined in Moscow. We consider the problems raised in the message as very serious,

15

since they are dealing with the basic issues of our collaboration.

In the spirit of sincerity, characteristic for our bilateral relations, we would like to

mention that we are surprised by its tone and the accusations regarding the position and role of

the Soviet Union with respect to the events taking place in Timisoara. We reject wholeheartedly

the statements with regard to the anti-Romanian campaign supposedly taking place in the Soviet

Union, not to mention the accusation that the actions against Romania have allegedly planned by

the Warsaw Treaty Organization [WTO]. Such accusations are unfounded and absolutely

unacceptable. Just as absurd are the declarations of certain Romanian officials who are suggesting

that the Soviet Union is preparing to intervene in Romania. We are starting, invariably, from the

idea that, in our relations with allied nations, as well as with all other nations, the principles of

sovereignty, independence, equality of rights, non-intervention in the internal affairs. These

principles have been once again confirmed during the [WTO] Political Consultative Committee

summit in Bucharest.

It is clear that the dramatic events taking place in Romania are your own internal

problem. The fact that during these events deaths have occured has aroused deep grief among the

Soviet public. The declaration adopted by the Congress of the People’s Deputies is also a

reflection of these sentiments.

Furthermore, I would like to inform you that our representative at the UN Security

Council has received instructions to vote against convening the Security Council for [the purpose

of] discussing the situation in Romania, as some countries have proposed. We consider that this

would be an infringement of the sovereignty of an independent state by an international

organization.

We want to hope that, in the resolution of the events in Romania, wisdom and realism

will prevail and that political avenues to solve the problems to the benefit of [our] friend, the

Romanian nation, will be found.

Our position comes out of our sincere desire not to introduce into our relationship

elements of suspicion or mistrust, out of our desire to continue our relations normally, in the

interest of both our nations, [and in the interest of] the cause of peace and socialism.

I. P. Aboimov asked that this message be sent immediately to Bucharest.

(ss) [Ambassador] Ion Bucur

[Source: Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs— Arhivele Ministerului Afacerilor Externe

(AMAE), Telegrame, Folder Moscow/1989, vol. 10, pp. 324-325. Translated for CWIHP by

Mircea Munteanu]

15

Ceausescu had accused the Soviet leadership, in cooperation with “other Warsaw Pact members” of

masterminding the events taking place in Timisoara, and of preparing an attack on Romania.

—————————————————————————————————————-

e-Dossier No. 5

New Evidence on the 1989 Crisis in Romania

Documents Translated and Introduced

by Mircea Munteanu

1

Recently released Romanian documents translated by the Cold War International History

Project (CWIHP) shed new light on how, in December 1989, the dramatic albeit mostly peaceful

collapse of Eastern Europe’s communist regimes came to its violent crescendo with the toppling

and execution of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. Following Solidarity’s electoral victory

in Poland, the demise of Communist authority in Hungary, the fall of Erich Honecker, a close

friend and ally of Ceausescu, and, finally, the deposing of Bulgaria’s Todor Zhivkov, Romania

had remained the last Stalinist bulwark in Eastern Europe. Much to everybody’s surprise,

however, an explosion of popular unrest in mid December 1989 over Securitate actions in

Timisoara quickly engulfed the Ceausescu regime, leading to the dictator’s ouster and execution.

CWIHP previously documented from Russian sources how, confronted with the violent

turmoil in Romania, the US administration sought intervention by the Soviet Union on behalf of

the oppositionforces. On Christmas Eve, 24 December 1989, with Moscow some eight hours

ahead of Washington, US Ambassador Jack Matlock went to the Soviet Foreign Ministry and met

with Deputy Foreign Minister I. P. Aboimov. According to the Soviet documents, the message

Matlock delivered— while veiled in diplomatic indirection— amounted to an invitation for the

Soviets to intervene in Romania. The Russian documents recorded that Matlock, apparently on

instructions from Washington, “suggested the following option: what would the Soviet Union do

if an appropriate appeal came from the [opposition] Front? He let us know that under the present

circumstances the military involvement of the Soviet Union in Romanian affairs might not be

regarded in the context of ‘the Brezhnev doctrine.’” Repudiating “any interference in the

domestic affairs of other states,” Aboimov— probably referring to the then ongoing US invasion

of Panama— proposed instead “that the American side may consider that ‘the Brezhnev doctrine’

is now theirs as our gift.”

2

The newly accessible Romanian documents, obtained by Romanian historians Vasile

Preda and Mihai Retegan, bring to light the Soviet reaction to the Romanian events in Timisoara

and Bucharest through the perspective of the Romanian ambassador in Moscow, Ion Bucur. His

cables, now declassified, illustrate the isolated and paranoid stance of the Ceausescu regime at the

height of its final crisis.

The events of December 1989 in Romania started, inconspicuously enough, with the

attempted relocation of the ethnic Hungarian Calvinist pastor László Tökés from his parish in

Timisoara. The failed attempts of the police (Militia) forces, joined by the secret police

(Securitate), to remove the pastor from his residence enraged the local population. Dispelling the

so-called “historical discord” between Hungarians and Romanians in the border region, the

population of Timisoara united together to resist the abuses of the regime.

Ceausescu’s reaction was a violent outburst. Blaming “foreign espionage agencies” for

inciting “hooligans” the ordered the Militia, the Securitate, the patriotic guards and the army to

use all force necessary to repress the growing challenge to the “socialist order.” The repression

caused over 70 deaths in the first few days alone; hundreds suffered injuries. By 20 December

however, it became clear that the popular uprising could not be put down without causing

massive casualties, an operation which the army did not want to undertake while Ceausescu was

1

For more information, please contact the CWIHP at Coldwar1@wwic.si.edu or 202.691.4110 or Mircea

Munteanu at MunteanuM@wwic.si.edu or 202.691.4267

2

See Thomas Blanton, “When did the Cold War End” in CWIHP Bulletin #10, (March 1998) pp. 184-191.

| Page 3 |

out of the country. After the army withdrew in the barracks on 20 December, the city was

declared “liberated” by the demonstrators.

Ceausescu returned from a trip in Iran on 20 December and immediately convened a

session of the Politburo. He demanded that a demonstration be organized in Bucharest

showcasing the support of the Bucharest workers for his policies. The demonstration proved to be

a gross miscalculation. The popular resentment had, by that time, reached a new peak: The

demonstration quickly degenerated into chaos and erupted in an anti-Ceausescu sentiment. The

violent suppression of the Bucharest unrest rivaled that of Timisoara.

3

Securitate, police and army

forces fired live ammunition into the population in Piata Universitatii (University Plaza) and

close to Piata Romana (Roman Square).

The following documents show the attempts of the Romanian regime to maintain secrecy

on the events taking place in Romania— even with regard to its increasingly estranged Soviet ally.

From restricting the access of Russian tourists in Romania beginning with 18 December

4

(Document No. 1) to the demands made by the Romanian embassy in Moscow to the Soviet

leadership to prevent the Soviet media from publishing news reports about “alleged events”

taking place in Timisoara, Cluj and, later, Bucharest (Documents Nos. 4 and 5),Bucharest sought

to limit the damage to the regime’s image of stability. Afraid that information about the events

taking place in Romania would tarnish Ceausescu’s image of “a world leader,” the Foreign

Ministry instructed the Romanian embassies not to respond to any questions concerning the

“alleged” events and demanded that all actions taken by the Romanian government were

legitimate by virtue of its sovereignty. (Document No. 2).

The documents also present a picture of a regime grasping at straws, accusing even

former allies of conspiracy, and believing that isolation would insure its survival. Ceausescu’s

longstanding hysteria about the machinations of “foreign espionage agencies” — and his growing

mistrust towards Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev— reached new heights in his accusation that

turmoil in Romania was used by the Warsaw Pact to oust him (Ceausescu) from office, a

suggestion that struck Aboimov as utter “insanity.” (Documents Nos. 5 and 7). Quite the

contrary, the US-Soviet conversations suggest, was actually the case.

3

Official statistics place the death figure at 162 dead (73 in Timisoara, 48 in Bucharest, and 41 in the rest

of the country) and 1107 wounded (of which 604 in Bucharest alone).

4

There were persistent rumors, during and after the 1989 events in Romania that the Soviet KGB sent

numerous agents in Romania in December 1989. Some accounts accused the KGB of attempting to

destabilize the regime while others accused them of attempting to shore it up. Likely both accounts are

somewhat exaggerated. While it is clear that the KGB was interested in obtaining information about the

events, it is unlikely that it attempted to interfere, either way in the unfolding of the events. It is more likely

that the closing of the borders both with the USSR but also with Hungary and Yugoslavia, is likely that

stranded numerous transistors on Romanian territory.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged: decembrie 1989, General Iulian Vlad, Mircea Munteanu, New Evidence on the 1989 Crisis in Romania, nicolae ceausescu, turisti rusi, Un Risc Asumat Filip Teodorescu, Wilson Center CWIHP | 3 Comments »

Romania 1989 (Video, filmata de un membru al asociatiei 21 decembrie 1989, si ignorata de Teodor Maries): “Munitie folosita de Teroristi in Decembrie 1989!” si “Teroristi Straini si Romani raniti in acelasi Spital cu Victimele lor”

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on March 6, 2010

In general, membrii si sustinatorii Asociatiei 21 decembrie 1989 neaga cu insistenta existenta teroristilor in decembrie 1989. Iata, de exemplu, comentarile lui Lucian Alexandrescu aici http://www.piatauniversitatii.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=21&t=1142): de Lucian Alexandrescu » Lun Iun 22, 2009 6:03 pm Toata vorbaraia, cu gloantedum-dum si cu cap vidia, nu are decat rolul de a mai adauga un vreasc la rugul, pe care trebuie pus dl. grl. Dan Voinea, pentru ca a comis erezia de a demonta legendele alcatuite de diversi regizori si in plus a indraznit sa mai comita si blasfemia de a cerceta penal pe marele edec.

In contextul acesta, e foarte interesant videourile filmate in decembrie 1989 de catre un alt membru/sustinator al asociatiei. E clar ca acest om nu este un spijinator al fostilor comunisti, al Frontului, sau al dlui Ion Iliescu http://alexandru2006.spaces.live.com/. Dar atentie, cum descrie videourile aceste: “Munitie folosita de Teroristi in Decembrie 1989!” si “Teroristi Straini si Romani raniti in acelasi Spital cu Victimele lor.” Din pacate in versiunea aceasta (cea mai noua postare pe youtube), prima a fost vazuta de 131 vizitatori, si a doua de catre 850 vizitatori, fara nici un coment. Iata videourile:

…

Teodor Maries vorbeste asa despre filmele facute in CC-ul in aceste zile…

“Au fost sute de arme date civililor la Revolutie. Numai eu am strans, in dupa-masa zilei de 22 decembrie, doua camere pline de arme. Eu am ajuns primul la etajul 6 al Comitetului Central, cu arma in mana. Am adunat acolo armele, ca sa nu ne impuscam. Probez cu declaratii. Este totul filmat cand se vede ca am coborat in hol cu un ofiter, iar el a spus ca rupe o foaie dintr-o carte aruncata acolo pe jos, ca sa putem face o evidenta a armelor si sa le putem cara. Au navalit toti acolo si au luat toate armele, inclusiv copii de 14 ani care aveau baionete in mana”, a declarat Teodor Maries…

Oare a vazut si el, dl. Maries, aceste gloante dum-dum si vidia in CC-ul? Ar fi interesant sa aflam care este opinia d-lui Doru Maries in legatura cu aceste filme de mai sus, nu?…

Posted in raport final, Uncategorized | Tagged: asociatia 21 decembrie 1989, dan voinea, decembrie 1989, decembrie 1989 video, documente declasaficate, documente desecretizate, Doru Maries, munitie folosita de teroristi in decembrie 1989, Raportul Final, romania 1989 video, sorin iliesiu, teodor maries, Teroristi Straini si Romani raniti in acelasi Spital cu Victimele lor, teroristii decembrie 1989 | Leave a Comment »

decembrie 1989: razboiul radioelectronic, “poate ca in realitate era un simplu joc pe calculator”…poate ca NU (II)

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on January 7, 2010

articole citate in partea I-a

9 ianuarie 1990; 11-17 ianuarie 1990

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged: decembrie 1989, razboiul radioelectronic, romania 1989, teroristi decembrie 1989 | Leave a Comment »

(NEW for the 20th Anniversary) Bullets, Lies, and Videotape: The Amazing, Disappearing Romanian Counter-Revolution of December 1989 (Part II: “A Revolution, a Coup d’Etat, AND a Counter-Revolution”) by Richard Andrew Hall

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on December 22, 2009

for Part I see His name was Ghircoias…Nicolae Ghircoias

Bullets, Lies, and Videotape:

The Amazing, Disappearing Romanian Counter-Revolution of December 1989

by Richard Andrew Hall, Ph.D.

Standard Disclaimer: All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) or any other U.S. Government agency. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying U.S. Government authentication of information or CIA endorsement of the author’s views. This material has been reviewed by CIA to prevent the disclosure of classified information. [Submitted 19 November 2009; PRB approved 15 December 1989]

I am an intelligence analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency. I have been a CIA analyst since 2000. Prior to that time, I had no association with CIA outside of the application process.

Part II

Romania, December 1989: a Revolution, a Coup d’etat, AND a Counter-Revolution

This December marks twenty years since the implosion of the communist regimeof Dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. [1] It is well-known, but bears repeating: Romania not only came late in the wave of communist regime collapse in the East European members of the Warsaw Pact in the fall of 1989 (Poland, Hungary, the GDR, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria), it came last—and inevitably that was significant.[2] Despite the more highly personalist (vs. corporate) nature of the Ceausescu regime, the higher level of fear and deprivation that characterized society, and the comparative insulation from the rest of the East European Warsaw Pact states, Romania could not escape the implications of the collapse of the other communist party-states.[3] Despite the differences, there simply were too many institutional and ideological similarities, or as is often most importantly the case, that is how members of both the state and society interpreted matters. “Going last” [in turn, in show] almost inevitably implies that the opportunities for mimicry, for opportunism, for simulation[4] on the one hand and dissimulation[5] on the other, are greater than for the predecessors…and, indeed, one can argue that some of what we saw in Romania in December 1989 reflects this.

Much of the debate about what happened in December 1989 has revolved around how to define those events…and their consequences.[6] [These can be analytically distinct categories and depending on how one defines things, solely by focusing on the events themselves or the consequences, or some combination thereof, will inevitably shape the answer one gets]. The primary fulcrum or axis of the definitional debate has been between whether December 1989 and its aftermath were/have been a revolution or a coup d’etat. But Romanian citizens and foreign observers have long since improvised linguistically to capture the hybrid and unclear nature of the events and their consequences. Perhaps the most neutral, cynical, and fatalistic is the common “evenimentele din decembrie 1989”—the events of December 1989—but it should also be pointed out that the former Securitate and Ceausescu nostalgics have also embraced, incorporated and promoted, such terminology. More innovative are terms such as rivolutie (an apparent invocation of or allusion to the famous Romanian satirist Ion Luca Caragiale’s 1880 play Conu Leonida fata cu reactiunea[7] , where he used the older colloquial spelling revulutie) or lovilutie (a term apparently coined by the humorists at Academia Catavencu, and combining the Romanian for coup d’etat, lovitura de stat, and the Romanian for revolution, revolutie).

The following characterization of what happened in December 1989 comes from an online poster, Florentin, who was stationed at the Targoviste barracks—the exact location where Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu would be summarily tried and executed on 25 December 1989. Although his definitions may be too economically-based for my taste—authoritarianism/dictatorship vs. democracy would be preferable—and the picture he presents may be oversimplified at points, the poster’s characterization shows that sometimes the unadorned straighttalk of the plainspoken citizen can cut to the chase better than many an academic tome:

I did my military service, in Targoviste, in fact in the barracks at which the Ceausescu couple were executed…It appears that a coup d’etat was organized and executed to its final step, the proof being how the President of the R.S.R. (Romanian Socialist Republic) died, but in parallel a revolution took place. Out of this situation has transpired all the confusion. As far as I know this might be a unique historical case, if I am not mistaken. People went into the streets, calling not just for the downfall of the president then, but for the change of the political regime, and that is what we call a revolution. This revolution triumphed, because today we have neither communism, nor even neocommunism with a human face. The European Union would not have accepted a communist state among its ranks. The organizers of the coup d’etat foresaw only the replacement of the dictator and the maintenance of a communist/neocommunist system, in which they did not succeed, although there are those who still hope that it would have succeeded. Some talk about the stealing of the revolution, but the reality is that we live in capitalism, even if what we have experienced in these years has been more an attempt at capitalism, orchestrated by an oligarchy with diverse interests…[8]

This is indeed the great and perhaps tragic irony of what happened in December 1989 in Romania: without the Revolution, the Coup might well have failed,[9] but without the Coup, neither would the Revolution have succeeded. The latter is particularly difficult for the rigidly ideological and politically partisan to accept; yet it is more than merely a talking point and legitimating alibi of the second-rung nomenklatura who seized power (although it is that too). The very atomization of Romanian society[10] that had been fueled and exploited by the Ceausescu regime explained why Romania came last in the wave of Fall 1989, but also why it was and would have been virtually impossible for genuine representatives of society—led by dissidents and protesters—to form an alternative governing body on 22 December whose decisions would have been accepted as sufficiently authoritative to be respected and implemented by the rump party-state bureaucracy, especially the armed forces and security and police structures. The chaos that would have ensued—with likely multiple alternative power centers, including geographically—would have likely led to a far greater death toll and could have enabled those still betting on the return of the Ceausescus to after a time reconquer power or seriously impede the functioning of any new government for an extended period.

The fact that the Revolution enabled the coup plotters to seize power, and that the coup enabled the Revolution to triumph should be identified as yet another version—one particular to the idiosyncracies of the Romanian communist regime—of what Linz and Stepan have identified as the costs or compromises of the transition from authoritarian rule. In Poland, for example, this meant that 65 percent of the Sejm was elected in non-competitive elections, but given co-equal authority with the Senate implying that “a body with nondemocratic origins was given an important role in the drafting of a democratic constitution”; in fact, Poland’s first completely competitive elections to both houses of Parliament occurred only in October 1991, fully two years after the formation of the first Solidarity government in August 1989.[11] In Romania, this meant that second-rung nomenklaturists—a displaced generation of elites eager to finally have their day in the sun—who to a large extent still harbored only Gorbachevian perestroikist views of the changes in the system as being necessary, were able to consolidate power following the elimination of the ruling Ceausescu couple.

The self-description by senior Front officials (Ion Iliescu) and media promoters (such as Darie Novaceanu in Adevarul) of the FSN (National Salvation Front) as the “emanation of the Revolution” does not seem justified. [12] It seems directly tied to two late January 1990 events—the decision of the Front’s leaders to run as a political party in the first post-Ceausescu elections and the contestation from the street of the Front’s leaders’ legitimacy to rule and to run in those elections. It also seems difficult to defend objectively as a legitimate description, since even according to their own accounts, senior Front officials had been in contact with one another and discussed overthrowing the Ceausescus prior to the Revolution, since there had existed no real competing non-Ceausescu regime alternative on 22 December 1989 (an argument they themselves make), and since they had clearly not been elected to office. Moreover, when senior former Front officials, Iliescu among them, point to their winning of two-thirds of the votes for the new parliament in May 1990 and Iliescu’s 85 percent vote for the presidency, the numbers in and of themselves—even beyond the by now pretty obvious and substantiated manipulation, surveillance, and intimidation of opposition parties, candidates, movements and civil society/non-governmental organizations that characterized the election campaign—are a red flag to the tainted and only partly free and fair character of those founding elections.

But if the FSN and Ion Iliescu cannot be accurately and legitimately described as the “emanation of the Revolution,” it also seems reasonable to suggest that the term “stolen revolution”[13] is somewhat unfair. The term “stolen revolution” inevitably suggests a central, identifiable, and sufficiently coherent ideological character of the revolution and the presence of an alternative non-Ceausescu, non-Front leadership that could have ensured the retreat of Ceausescu forces and been able to govern and administer the country in the days and weeks that followed. The absence of the latter was pretty clear on 22 December 1989—Iasi, Timisoara, and Arad among others, had local, authentic nuclei leading local movements (for example, the FDR, Frontul Democrat Roman), but no direct presence in Bucharest—and the so-called Dide and Verdet “22 minute” alternative governments were even more heavily compromised by former high-ranking communist dignitary inclusion than the FSN was (the one with the least, headed by Dumitru Mazilu, was rapidly overtaken and incorporated into the FSN).

As to the question of the ideological character of the revolt against Ceausescu, it is once again instructive to turn to what a direct participant, in this case in the Timisoara protests, has to say about it. Marius Mioc[14], who participated in the defense of Pastor Tokes’ residence and in the street demonstrations that grew out of it, was arrested, interrogated, and beaten from the 16th until his release with other detainees on the 22nd and who has written with longstanding hostility toward former Securitate and party officials, IIiescu, the FSN, and their successors, gives a refreshingly honest account of those demonstrations that is in stark contrast to the often hyperpoliticized, post-facto interpretations of December 1989 prefered by ideologues:

I don’t know if the 1989 revolution was as solidly anticommunist as is the fashion to say today. Among the declarations from the balcony of the Opera in Timisoara were some such as “we don’t want capitalism, we want democratic socialism,” and at the same time the names of some local PCR [communist] dignitaries were shouted. These things shouldn’t be generalized, they could have been tactical declarations, and there existed at the same time the slogans “Down with communism!” and flags with the [communist] emblem cut out, which implicitly signified a break from communism. [But] the Revolution did not have a clear ideological orientation, but rather demanded free elections and the right to free speech.[15]

Romania December 1989 was thus both revolution and coup, but its primary definitive characteristic was that of revolution, as outlined by “Florentin” and Marius Mioc above. To this must be added what is little talked about or acknowledged as such today: the counter-revolution of December 1989. Prior to 22 December 1989, the primary target of this repression was society, peaceful demonstrators—although the Army itself was both perpetrator of this repression but also the target of Securitate forces attempting to ensure their loyalty to the regime and their direct participation and culpabilization in the repression of demonstrators. After 22 December 1989, the primary target of this violence was the Army and civilians who had picked up weapons, rather than citizens at large. It is probably justified to say that in terms of tactics, after 22 December 1989, the actions of Ceausist forces were counter-coup in nature, contingencies prepared in the event of an Army defection and the possibility of foreign intervention in support of such a defection. However, precisely because of what occurred prior to 22 December 1989, the brutal, bloody repression of peaceful demonstrators, and because the success of the coup was necessary for the success of the revolution already underway, it is probably accurate to say that the Ceausescu regime’s actions as a whole constituted a counter-revolution. If indeed the plotters had not been able to effectively seize power after the Ceausescus fled on 22 December 1989 and Ceausescu or his direct acolytes had been able to recapture power, we would be talking of the success not of a counter-coup, but of the counter-revolution.

A key component of the counter-revolution of December 1989 concerns the, as they were christened at the time, so-called “terrorists,” those who were believed then to be fighting in defense of the Ceausescu couple. It is indeed true as Siani-Davies has written that the Revolution is about so much more than “the Front” and “the terrorists.”[16] True enough, but the outstanding and most vexing question about December 1989—one that resulted in 942 killed and 2,251 injured after 22 December 1989—is nevertheless the question of “the terrorists.” Finding out if they existed, who they were, and who they were defending remains the key unclarified question of December 1989 two decades later: that much is inescapable.[17]

[1]The hyperbolic and popular academic designation of the Ceausescu regime as Stalinist is not particularly helpful. Totalitarian yes, Stalinist no. Yes, Nicolae Ceausescu had a Stalinist-like personality cult, and yes he admired Stalin and his economic model, as he told interviewers as late as 1988, and we have been told ad nauseum since. But this was also a strange regime, which as I have written elsewhere was almost characterized by a policy of “no public statues [of Ceausescu] and no (or at least as few as possible) public martyrs [inside or even outside the party]”—the first at odds with the ubiquity of Nicoale and Elena Ceausescus’ media presence, the second characterized by the “rotation of cadres” policy whereby senior party officials could never build a fiefdom and were sometimes banished to the provinces, but almost were never eliminated physically, and by Ceausescus’ general reluctance to “spoil” his carefully created “image” abroad by openly eliminating high-profile dissidents (one of the reasons Pastor Tokes was harassed and intimidated, but still alive in December 1989) (see Richard Andrew Hall 2006, “Images of Hungarians and Romanians in Modern American Media and Popular Culture,” at http://homepage.mac.com/khallbobo/RichardHall/pubs/huroimages060207tk6.html). Ken Jowitt has characterized the organizational corruption and political routinization of the communist party as moving from the Stalinist era—whereby even being a high-level party official did not eliminate the fear or reality of imprisonment and death—to what he terms Khrushchev’s de facto maxim of “don’t kill the cadre” to Brezhnev’s of essentially “don’t fire the cadre” (see Ken Jowitt, New World Disorder: The Leninist Extinction, especially pp. 233-234, and chapter 4 “Neotraditionalism,” p. 142). The very fact that someone like Ion Iliescu could be around to seize power in December 1989 is fundamentally at odds with a Stalinist system: being “purged” meant that he fulfilled secondary roles in secondary places, Iasi, Timisoara, the Water Works, a Technical Editing House, but “purged” did not threaten and put an end to his existence, as it did for a Kirov, Bukharin, and sadly a cast of millions of poor public souls caught up in the ideological maelstorm. Charles King wrote in 2007 that “the Ceausescu era was the continuation of Stalinism by other means, substituting the insinuation of terror for its cruder variants and combining calculated cooptation with vicious attacks on any social actors who might represent a potential threat to the state” (Charles King, “Remembering Romanian Communism,” Slavic Review, vol. 66, no. 4 (Winter 2007), p. 720). But at a certain point, a sufficient difference in quantity and quality—in this case, of life, fear, imprisonment, and death—translates into a difference of regime-type, and we are left with unhelpful hyperbole. The level of fear to one’s personal existence in Ceausescu’s Romania—both inside and outside the party-state—simply was not credibly comparable to Stalin’s Soviet Union, or for that matter, even Dej’s Romania of the 1950s. In the end, Ceausescu’s Romania was “Stalinist in form [personality cult, emphasis on heavy industry], but Brezhnevian in content [“don’t fire the cadres”…merely rotate them…privileges, not prison sentences for the nomenklatura].”

[2] For a recent discussion of the “diffusion” or “demonstration” effect and regime change, see, for example, Valerie Bunce and Sharon Wolchik, “International Diffusion and Postcommunist Electoral Revolutions,”

Communist and Postcommunist Studies, vol. 39, no. 3 (September 2006), pp. 283304.

[3] For more discussion, see Hall 2000.

[4]For discussion of the term see Michael Shafir, Romania: Politics, Economics, and Society (Boulder, 1985).

[5]For discussion of the term see Ken Jowitt, New World Disorder (University of California Berkely Press, 1992).

[6] For earlier discussions of this topic from a theoretical perspective , see, for example, Peter Siani-Davies, “Romanian Revolution of Coup d’etat?” Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 29, no. 4 (December 1996), pp. 453-465; Stephen D. Roper, “The Romanian Revolution from a Theoretical Perspective,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 27, no. 4 (December 1994), pp. 401-410; and Peter Siani-Davies, The Romanian Revolution of December 1989, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), pp. 1-52 ff, but especially (chapter 7) pp. 267-286. For a recent effort to deal with this question more broadly, see Timothy Garton Ash, “Velvet Revolution: The Prospects, The New York Review of Books, Volume 56, Number 19 (December 3, 2009) at http://www.nybooks.com/articles/23437. For a good comparison and analysis of public opinion polling performed in 2009 and 1999 about classifying what happened in December 1989, see Catalin Augustin Stoica in http://www.jurnalul.ro/stire-special/a-fost-revolutie-sau-lovitura-de-stat-527645.html.

[7] http://ro.wikisource.org/wiki/Conu_Leonida_fa%C5%A3%C4%83_cu_reac%C5%A3iunea

[8] Entry from forum at http://www.gds.ro/Opinii/2007-12-20/Revolutia:+majoratul+rusinii!

[9]This is a point that was first made credibly by Michael Shafir in Michael Shafir, “Preparing for the Future by Revising the Past,” Radio Free Europe Report on Eastern Europe, vol. 1, no. 41 (12 October 1990). It becomes all the clearer, however, when we consider that the XIV PCR Congress from 20-24 November 1989 went off without the slightest attempt at dissidence within the congress hall—a potential opportunity thereby missed—and that the plotters failed to act during what would have seemed like the golden moment to put an end to the “Golden Era,” the almost 48 hours that Nicolae Ceausescu was out of the country in Iran between 18 and 20 December 1989, after regime forces had already been placed in the position of confronting peaceful demonstrators and after they opened fire in Timisoara. In other words, an anti-regime revolt was underway, and had the coup been so minutely prepared as critics allege, this would have been the perfect time to seize power, cut off the further anti-system evolution of protests, exile Ceausescu from the country, and cloak themselves in the legitimacy of a popular revolt. What is significant is that the plotters did not act at this moment. It took the almost complete collapse of state authority on the morning of 22 December 1989 for them to enter into action. This is also why characterizations of the Front as the ‘counterstrike of the party-state bureaucracy’ or the like is only so much partisan rubbish, since far from being premised as something in the event of a popular revolt or as a way to counter an uprising, the plotters had assumed—erroneously as it turned out—that Romanian society would not rise up against the dictator, and thus that only they could or had to act. It is true, however, that once having consolidated power, the plotters did try to slow, redirect, and even stifle the forward momentum of the revolution, and that the revolutionary push from below after December 1989 pushed them into reforms and measures opening politics and economics to competition that they probably would not have initiated on their own.

[10] I remain impressed here by something Linz and Stepan highlighted in 1996: according to a Radio Free Europe study, as of June 1989 Bulgaria had thirteen independent organizations, all of which had leaders whose names were publicly known, whereas in Romania there were only two independent organizations with bases inside the country, neither of which had publicly known leaders (Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p. 352). For more discussion of this and related issues, see Hall 2000.

[11] The presidency was also an unelected communist holdover position until fall 1990. See Linz and Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe, pp. 267-274.

[12] For a discussion of the roots and origins of these terms, see Matei Calinescu and Vladimir Tismaneanu, “The 1989 Revolution and Romania’s Future,” Problems of Communism, vol. XL no. 1-2 (January-April 1991), p. 52, especially footnote no. 38.

[13] Stephen Kotkin associates the concept, accurately if incompletely, with Tom Gallagher and Vladimir Tismaneanu in Stephen Kotkin, Uncivil Society: 1989 and the Implosion of the Communist Establishment (Modern Library Chronicles, 2009), pp. 147-148 n. 1. Similar concepts have taken other names, such as “operetta war” (proposed but not necessarily accepted) by Nestor Ratesh, Romania: The Entangled Revolution (Praeger, 1991) or “staging of [the] revolution” [advocated] by Andrei Codrescu, The Hole in the Flag (Morrow and Company, 1991). Dumitru Mazilu’s 1991 book in Romanian was entitled precisely “The Stolen Revolution” [Revolutia Furata]. Charles King stated in 2007 that the CPADCR Report “repeats the common view (at least among western academics) of the revolution as being hijacked,” a term essentially equating to “stolen revolution,” but as Tismaneanu headed the commission and large sections of the Report’s chapter on December 1989 use previous writings by him (albeit without citing where they came from), it is hard to somehow treat the Report’s findings as independent of Tismaneanu’s identical view (for an earlier discussion of all this, see Hall 2008)

[14] Mioc does not talk a great deal about his personal story: here is one of those few examples, http://www.timisoara.com/newmioc/5.htm.

[15] Quoted from http://mariusmioc.wordpress.com/2009/09/29/o-diferentiere-necesara-comunisti-si-criminali-comunisti/#more-4973

[16]Peter Siani-Davies, The Romanian Revolution of December 1989, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), p. 286.

Posted in raport final, Uncategorized | Tagged: Academia Catavencu, andrei codrescu, Caragiale, Catalin Augustin Stoica, charles king, communism totalitarianism Stalinism, Conu Leonida fata cu reactiunea, decembrie 1989, FSN NSF National Salvation Front 1990, ion iliescu, Ken Jowitt, marius mioc, michael shafir, Nestor Ratesh, New World Disorder, nicolae ceausescu, peter siani-davies, Poland 1989, raport final, Richard Andrew Hall, Romania stolen revolution, securitate december 1989, slavic review romania, Stepan Linz democratic transitions, Stephen D. Roper, Stephen Kotkin, Targoviste decembrie 1989, teroristii 1989, The Leninist Extinction, the terrorists december 1989, Timothy Garton Ash, Tismaneanu report, Tom Gallagher, Uncivil Society 1989, vladimir tismaneanu | 5 Comments »

9 cazuri dintr-o tragedie: soldati si civili impuscati cu gloante dum-dum (aka gloante explozive) dupa 22 decembrie 1989 in Bucuresti (dovezi disponsibile pe Internetul)

Posted by romanianrevolutionofdecember1989 on December 21, 2009

Filoti Claudiu ( 172 ) Filoti Claudiu ( 172 )Profesie: Locotenent major la UM 01171 Buzau, capitan post-mortem Data nasteri: 30.07.1964 Locul nasterii: Vaslui Calitate: Erou Martir |

Data mortii: 22 decembrie 1989 Locul mortii: Bucuresti, zona MApN Cauza: Impuscat in torace cu gloante dum-dum Vinovati: Observatii: |

| : | |

Lupea Ioan Daniel ( 255 ) Lupea Ioan Daniel ( 255 )Profesie: Soldat in termen la UM 01929 Resita Data nasteri: 02.06.1970 Locul nasterii: Hunedoara Calitate: Erou Martir |

Data mortii: 24 decembrie 1989 Locul mortii: Resita, in dispozitivul de aparare al unitatii mil Cauza: Impuscat pe 23 decembrie 1989 cu un glont dum-dum, care a intrat pe deasupra piciorului stang si a iesit pe sub mana stanga Vinovati: Observatii: |